Scientists have discovered that comb jellies can fuse with other individuals of the same species as a way of healing from injury. This suggests these animals cannot recognize their own body from that of their comb jelly neighbors. What makes this evolutionarily possible?

By Sofia Caetano Avritzer

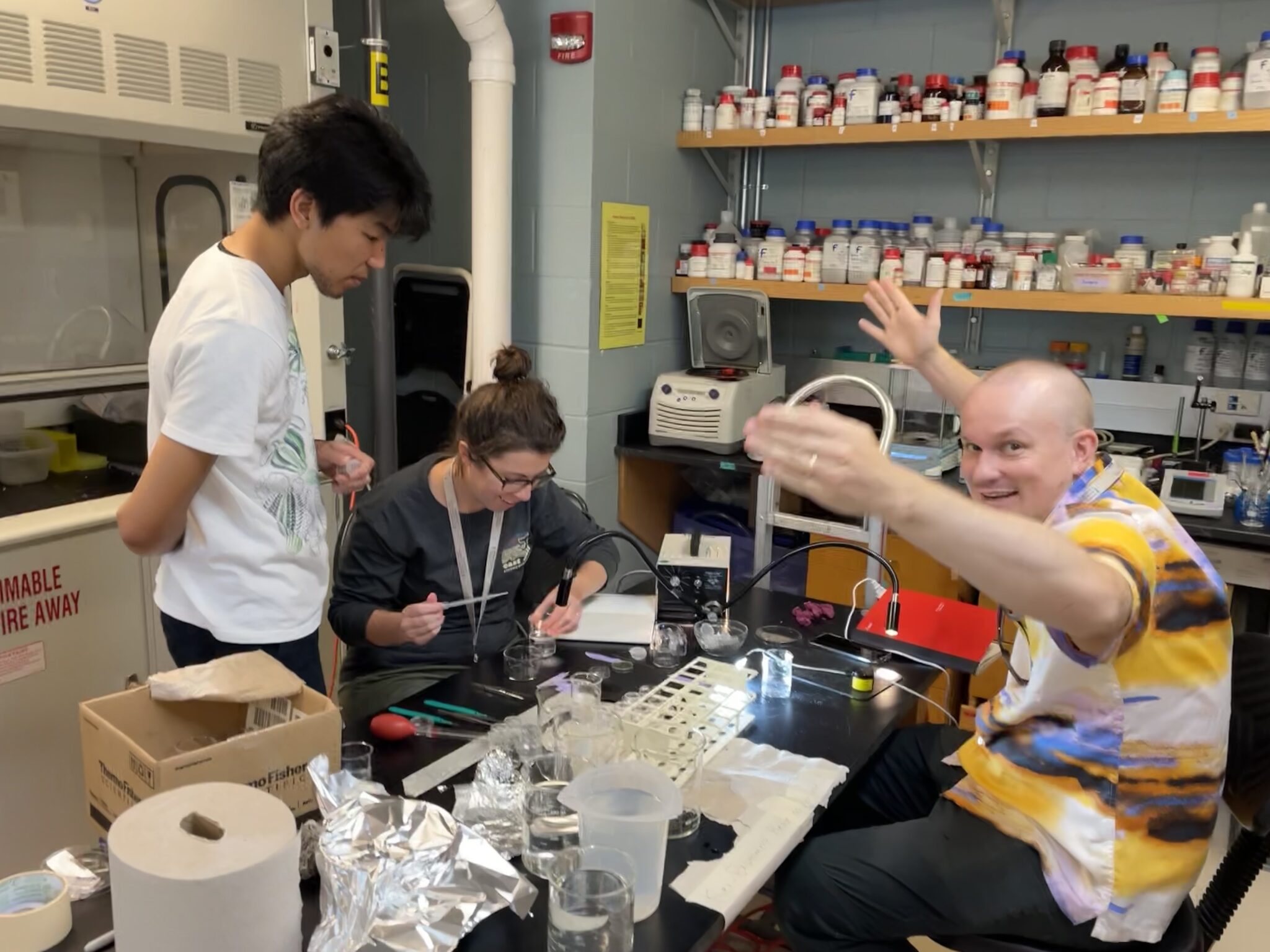

With four butts and two mouths, the creature floating in the beaker looked like a monster straight out of a B-horror movie. Kei Jokura had carried it into the lab at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and now a group of scientists huddled around it, mystified. Looking through a microscope, they realized that what seemed like a single bizarre animal was two ctenophores—also called comb jellies—that had fused together as a way of healing after injury.

This unexpected discovery, reported in a recent study published in Current Biology, suggests that comb jellies can’t tell their own body apart from that of other individuals of the same species. Scientists had assumed this differentiation ability, called allorecognition, was something almost all animals could do—it’s what causes our bodies to reject transplants from donors who are not a match.

What are comb jellies?

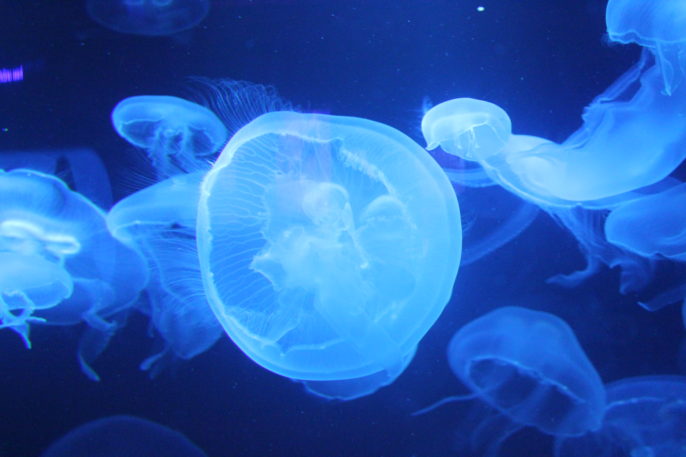

Comb jellies are marine invertebrates that look like stingless jellyfish, with gelatinous bodies sporting two tentacles—and two anuses. They get their name from the rows of tiny, hair-like structures that line the surface of their bodies, looking like the teeth on a comb, which they use to swim.

One of the oldest animals on Earth, scientists think that comb jellies are the sister group to all other animals—they separated more than 1.2 billion years ago from the common ancestor that originated everything from sponges to humans. Because of this, understanding comb jelly biology might give us clues on how early animals evolved into the creatures we know today.

Comb jellies were already well known for their powers of regeneration. Some species can regrow parts of their body, including damaged combs and tentacles. One particular species can even turn back from an adult into a larva when hurt. But scientists in this recent study found something even more remarkable than all this.

RELATED: Multitasking Sensory Neurons in the Brain of a Marine Invertebrate

The amazing marine blob

“We were working late one night when Kei walked in holding a beaker with this weird creature,” says Mariana Rodriguez-Santiago, one of the researchers in the study. They immediately gathered around the microscope to look at the strange animal.

The creature had all the exterior parts of a normal ctenophore—mouth, anuses, and tentacles—but every part was duplicated. None of the researchers had ever seen anything like it before, says Dr. Rodriguez-Santiago.

To figure out how this had happened, the researchers started by cutting up comb jellies and putting them in beakers of different sizes. They found that as long as the cut-up comb jellies were close enough together, they would fuse 90 percent of the time. These fused animals then functioned as a single unit. Food that was eaten by the mouth of one animal could come out the butts of the other, and no matter where you poked them, the whole animal would contract, showing that their nervous and digestive systems were also fused.

Mark Martindale, a marine biology professor at the University of Florida, was impressed at how well these comb jellies fused with each other. Dr. Martindale, who was not involved in the work, cautions that future studies are needed to understand how long these “monsters” can remain stable. “Do they eventually rip themselves apart?”

Where one ends and the other begins

Other than making for quirky-looking animals, this discovery showed something very surprising: comb jellies don’t have allorecognition, the ability to recognize their own bodies from that of other individuals of their same species. This suggests comb jellies might be a unique window into how an animal without that ability works, and how that capacity evolved over time in the ancestors of other animals, according to Dr. Rodriguez-Santiago.

In the future, the study researchers want to understand the limits of what comb jellies can recognize during regeneration—and snacking. “They eat other ctenophores, but not of their own species,” Dr. Rodriguez-Santiago says, “so I wonder if they can fuse with another species?”

RELATED: Jellyfish Do More than Drift

You might be disappointed, however, if you go looking for fused comb jellies while out swimming. “We don’t think that this is necessarily a feature that occurs in the wild,” says Dr. Rodriguez-Santiago. “They don’t really have a lot of reasons to bump into each other, which is maybe why they’ve never developed an allorecognition system.”

If you are the only comb jelly for miles, rest easy: you might just never have to figure out where you end and another comb jelly begins.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Current Biology.

References

Jokura, K., Anttonen, T., Rodriguez-Santiago, M., & Arenas, O. M. (2024). Rapid physiological integration of fused ctenophores. Current Biology, 34(19), PR889-R890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.07.084

Schultz, D. T., Haddock, S. H. D., Bredeson, J. V., Green, R. E., Simakov, O., & Rokhsar, D. S. (2023). Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals. Nature, 618, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05936-6

Soto-Angel, J. J., & Burkhardt, P. (2024). Reverse development in the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. PNAS, 121(45), e2411499121. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.09.606968

Featured image: Comb jelly spotted at The Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk. Photo by The Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk, licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

About the Author

Sofia Caetano Avritzer is a neuroscience PhD student at the Rockefeller University. When she is not in the lab, she loves talking and writing about science, visiting National Parks, and making pottery. She lives in NYC with her partner and two cats. Connect with her through X (formerly Twitter) @sofiavritzer.