Tiny plastic particles, or microplastics, have made their way from our soil, oceans, and bodies. Plastic pollution on the nanoscale can have dangerous new properties.

By Emily Rhode

Tiny plastic particles that can barely be seen by the human eye have made their way from our soil into everyday items we know—from earthworms to honey to the beer that we drink—bringing toxic chemicals with them wherever they go. The saying goes that what we can’t see can’t hurt us. Yet, what if these unseen particles are not only hurting us but also changing the entire course of biological evolution? Researchers in Germany have issued a new warning that these human-generated “microplastics” could potentially be wreaking environmental havoc right under our feet, and that ignoring the problem could have dire consequences.

“We think that there is a reasonable chance that inland waters and agricultural soils represent a larger portion of environmental microplastics compared to oceanic basins,” says Dr. Abel de Souza Machado of Freie Universität Berlin and IGB-Berlin. “However, this is based in limited evidence.” The scientists have made an urgent call for increased research into the effects of terrestrial microplastics, citing a small but growing body of evidence that they pose an emerging global threat to human and environmental health.

Plastic straws in the spotlight

Plastic pollution exploded into the public consciousness in April 2015 when a shockingly graphic video taken by marine biology doctoral student Christine Figgener went viral. The footage depicts an olive ridley sea turtle wincing in pain as scientists remove a full-size plastic drinking straw lodged in its left nostril.

The backlash from the video ballooned into a worldwide movement to ban single-use plastic straws. Film director Linda Booker was inspired to build on the straw-free campaign by creating a documentary film that she aptly named STRAWS. The film highlights plastic contamination in the oceans and follows the stories of school children, entrepreneurs, scientists, and artists who are working to solve the problem.

“I wanted to find a way to demonstrate a global problem in a way that was impactful, while also being careful not to overwhelm people. Straws are small and uncomplicated, but when you start informing people about the vast number of them used daily and that they are nonrecyclable, it helps start the conversation about consumption and production of plastics. Once people are made aware that billions are used only once daily, worldwide it becomes a “sticky” topic, and all the sudden they start to notice them wherever they go to eat/drink and much too often in streets, ditches, and on beaches as litter.”

Plastic pollution on the nanoscale

The plastic litter that ends up on the ground is exposed to water, sunlight, and even soil microbes. Eventually, it starts to break down. At less than 5 millimeters, these microplastics begin to move through the environment much differently than they did when they were part of a plastic bottle. Broken down into even smaller pieces, things start to get strange. At one ten-thousandth of a millimeter, plastics on the nanoscale can have new properties that look nothing like that original plastic bottle. And that can be dangerous.

“When you change the size of the plastic to the nanoscale, it changes the properties in ways that we don’t understand yet,” says Dr. Brian Chapman, a scientist who studies nanoparticles. “Some can be absorbed more readily into the body, even through skin. [They] can give off the toxic components more easily.” These toxins may be causing more harm than the pieces of plastic that can be seen.

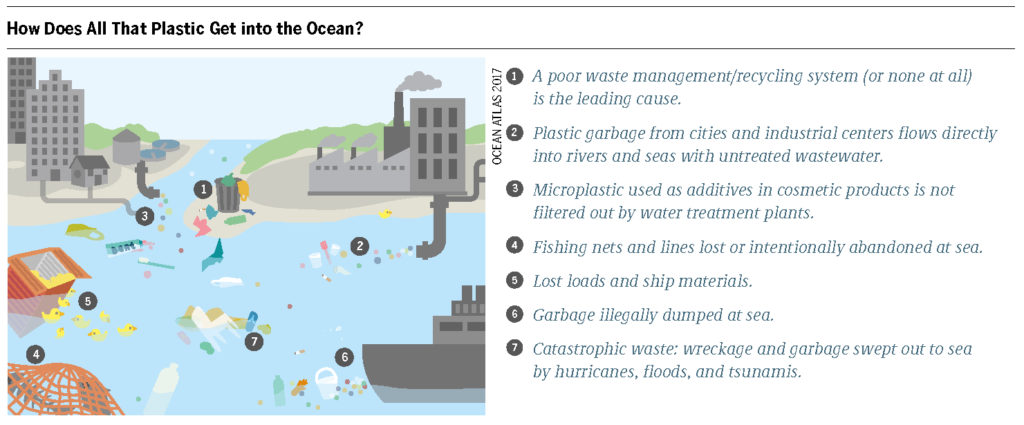

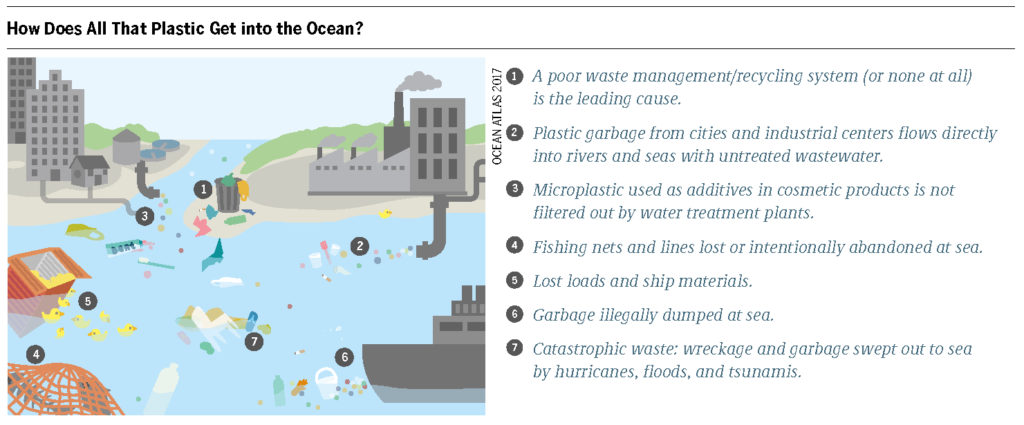

Micro- and nanoplastics have been well documented in marine ecosystems, showing up in huge “garbage patches” in the Pacific, in commercially harvested fish in the North Atlantic, and even in corals in the Great Barrier Reef. But ocean contamination might be just the tip of the plastic pollution iceberg. Some estimates put the amount of plastics that find their way into soils or inland waters at 32 percent of all plastic waste. Plastics from wastewater sludge that is applied to agricultural fields is one potentially large source. Aerosolized plastics from manufacturing plants is another. Despite several alarming studies about their effects on terrestrial environments, micro- and nanoplastics in soil have gone largely unstudied. “Continental systems have been understudied compared to aquatic because it is visually and methodologically easier to identify this contaminant in aquatic ecosystems,” explains Machado.

The consequences of plastic contamination

The completed research is troubling. When exposed to microplastics, earthworms showed changes in size and burrowing behavior in the soil. Microplastic exposure has also caused negative effects on the reproduction and growth of springtails, a common arthropod found in soil. The researchers fear that these are just some of the ways that human-generated plastic contamination could be putting evolutionary stress on organisms.

Plastic particles have been found in the beer we drink and the seafood we eat. When asked if plastics in soils could have more harmful effects on the environment than what we are already seeing in the oceans, Machado said that “it is very likely that not even all possible effects of microplastics in aquatic systems have been proposed. What we can say is that it is within terrestrial and continental systems that most of plastics are first produced, used, and disposed, and therefore they have first the chance to impact biota. Other attempts to compare potential effects in the marine and continental environment by now could be highly conceptual and not based on factual evidence.”

By eliminating plastics from our daily lives, experts believe that we can slow the accumulation of plastic pollution in the environment. “I hope in addition to straws, people will switch to nonplastic shopping bags, water bottles, carrying their own utensils, etc., and think more about the packaging options of their food and beverage purchases,” says Booker. “The next level is the other items in our households (especially kitchens) that used to be glass, metal, and wood and avoiding single-use plastic.” But until more scientific evidence is gathered, we are left to wonder what harm these unseen particles are causing, and what future dangers they may pose.

References

de Souza Machado, A. A., Kloas, W., Zarfl, C., Hempel, S., & Rillig, M. C. (2018). Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems. Global Change Biology, 24(4), 1405–1416. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14020.

Booker (Producer). (2017). STRAWS [Motion picture]. United States: By the Brook Productions, LLC. Film screening in Durham, North Carolina.

Featured photo: “Stop Trashing My Ocean” by Ingrid Taylar