How is climate change affecting migratory birds? A team of researchers offers an explanation.

In a study of more than 200 migratory bird species, scientists at the University of Cornell have made a yearlong tie between green vegetation and movements of certain migratory birds. The study also raises the question of how a changing climate will impact these seasonal visitors.

A chlorophyll correlation

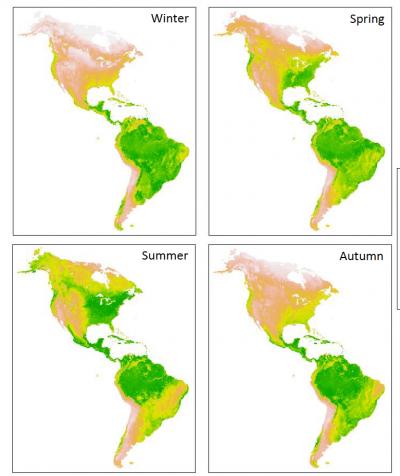

Using thirteen years of data collected through Cornell’s eBird platform, researchers Frank La Sorte and Catherine Graham aligned the patterns of migratory birds’ movements throughout the seasons with how much vegetation was occurring in North and South America at given times throughout the year.

The study took into account one of the biggest factors in any species’ migration: food and its availability. Graham and La Sorte compartmentalized 230 migratory bird species into seven “dietary guilds”, including meat eaters, plant eaters, seed eaters, insect eaters and nectar eaters.

Though bird species data was gathered with the help of citizen scientists, Graham and La Sorte used satellite imagery to recreate the greening and browning of vegetation across all four seasons.

Previously, it was hypothesized that migration and vegetation went hand-in-hand, and other studies have looked at correlations between the two phenomena during parts of the year. But this study is the first of its kind to match vegetation with bird migration across the entire Western hemisphere, throughout the entire year.

Help track migratory birds

Ecologists can now forecast bird migrations like meteorologists forecast the weather. But without on-the-ground citizen science observations, it’s hard to tell a songbird from a goose. You can help.

REVOLUTIONIZING BIRD WATCHING WITH RADAR

Migratory birds on the move

Of all the different diets and seasonal movements among the bird species studied, Graham and La Sorte found the strongest correlation between herbivore and granivore, or seed-eating, birds during spring migration.

“You could say they follow the ‘green wave’ north in the spring and then follow it in reverse during the fall, keeping pace with a wave that is retreating ahead of the North American winter,” La Sorte says.

On the other hand, some correlations fell through. For example, the migration patterns of carnivorous birds like hawks and eagles didn’t align with vegetation changes in the western U.S. Insectivores in the eastern part of the study area also misaligned with shifts in vegetation, which the researchers think has to do with the Gulf of Mexico; across all that open water, it’s hard to see what plants are cropping up in the spring or dying back in the fall.

RELATED: WHY ARE EGGSHELLS SO STRONG?

Even birds that don’t eat plants directly are impacted by what is growing, where and when. For instance, changes in vegetation can impact when small rodents come out from hibernation, which affects the birds that prey on small rodents. Flowers blooming at certain points may attract (or repel) particular insects, and in turn attract the predators that eat them.

Changing canopies

According to the study, greening in the spring is controlled in part by precipitation, while vegetation in the fall is related to daylight hours. Both spring and fall vegetation are affected by temperature, though, which has ominous implications in the context of climate change.

Evidence already exists that climate change is impacting seasonal vegetation changes. In many areas, this manifests as earlier springs, longer growing seasons and later autumns. It’s good news for the backyard gardener or those of us who don’t like winter, but can mean trouble for birds who time their migrations based on what food is usually available. Some birds might arrive too late or too early, which can throw their finely tuned cycles off-kilter.

“Unchecked climate change means it’s more likely that there will be a mismatch—migratory birds during stopover or when arriving on their breeding or wintering grounds could miss the peak food supply—no matter what they eat,” La Sorte says.

While this study solidifies a long-hypothesized pattern between plants and birds, the researchers believe it underscores the need to dive deeper into what cues animals into migrating—and what could happen to them if those signals shift.

It takes a village

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of this study is the sheer volume of data collected by citizen scientists observing their surroundings. For this study, the researchers accessed information from more than 28.5 million checklists in Cornell’s eBird database, which identified more than 4,500 different species.

RELATED: SUMATRAN TIGERS CLINGING TO SURVIVAL

The eBird platform collects information in a checklist format during specific recording events. Participants can mark down which birds they identify via sight or sound, then upload their recordings to the database.

And through the efforts of countless hours of observation and checked boxes, we now have concrete evidence that what plants start appearing where has a large effect on the birds many of us love seeing in our yards and forests each spring and fall. This study shows that even if they’ve never set foot in a lab, citizen scientists can play a valuable role in research and in the future of the planet as a whole, as we—alongside migratory birds—all face climate change together.

Do you want to join a citizen science project and help track migratory birds? Try one of these: Citizen Science Projects for the Birds.

This study was published in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

Reference

Sorte, F. A., & Graham, C. H. (2020). Phenological synchronization of seasonal bird migration with vegetation greenness across dietary guilds. Journal of Animal Ecology. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.13345

Featured photo of a Common redpoll by Helena Garcia, Quebec.

About the Author

Mackenzie Myers Fowler is a science writer, native Michigander, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again.