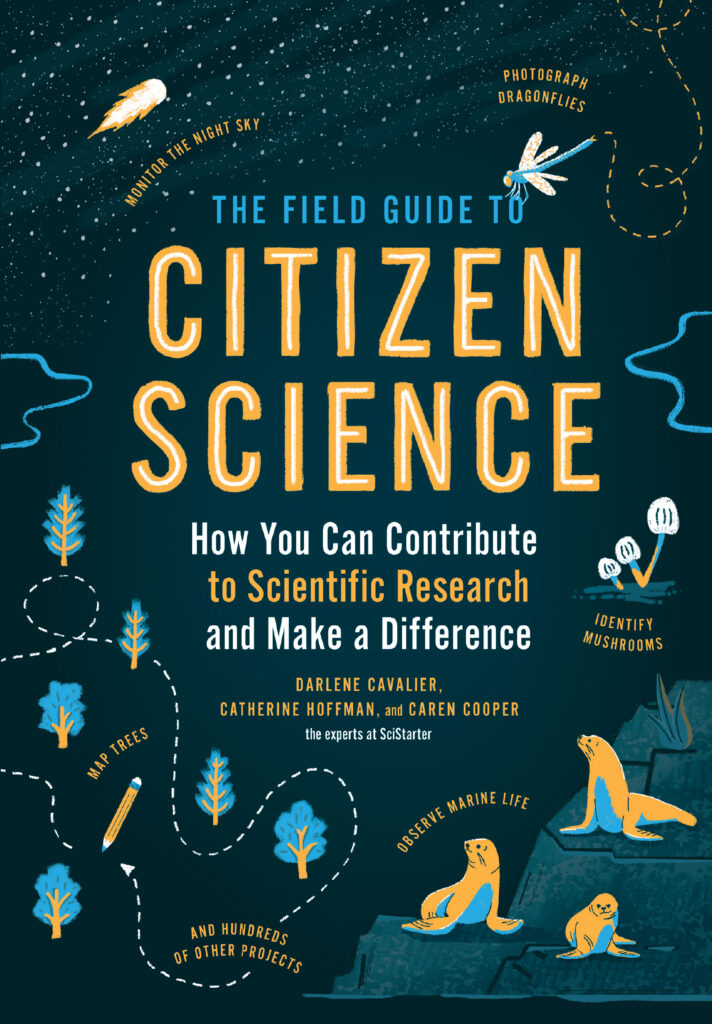

Darlene Cavalier, Catherine Hoffman, and Caren Cooper. The Field Guide to Citizen Science: How You Can Contribute to Scientific Research and Make a Difference, $7.60 Kindle, $11.99 Paperback

Reviewed by Devon Moriarty

I know you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but in this case, the front of The Field Guide to Citizen Science: How You Can Contribute to Scientific Research and Make a Difference effectively communicates the essence of this book. A simple black, blue, and yellow color scheme featuring equally accessible illustrations–meant to represent participatory possibilities in citizen science–graces the cover of this introductory get-started guide by SciStarter experts Darlene Cavalier, Catherine Hoffman, and Caren Cooper. Equal parts textbook, narrative, and guidebook, this book informs, fascinates, and most importantly, persuades readers to (mostly metaphorically, and sometimes literally) test the waters of citizen science. The clean design of the book isn’t just an aesthetic choice, but one that invites readers to write in margins and fold page corners. It’s clear that this is a book that’s meant to be used; not just read.

The beginning of an exploration into citizen science

Putting forth the purpose of the book in the Introduction, the authors recommend that you “treat this book as your field guide and the beginning of an exploration into citizen science.” They also encourage readers to complement the book with the use of SciStarter’s project database that allows users to “discover, join, and even track your contributions to projects.” SciStarter, of course, is the online citizen science community founded by one of the book’s authors, Darlene Cavalier, and the project database is the go-to place on the internet for novice and experienced citizen scientists alike looking to find the right project fit. From here, the book is divided up into six, easily digestible chapters; the first three provide the reader with a brisk orientation to citizen science, while the final three provide citizen science project overviews and direct readers to important resources.

Citizen science across time

The opening chapter on “The History and Future of Citizen Science” briefly orients novices to a field that spans centuries. Pointing first to recent shifts in policy and funding that have recognized the legitimacy of citizen science, the authors then look back to notable (citizen) scientists like Gregor Mendel and Charles Darwin, reflecting on how the credentials one needs to engage in scientific inquiry have evolved in tandem with the cultural landscape. It’s made clear that, contrary to popular belief, doing science has never been exclusively reserved for professionals in lab coats working in sanitized labs and has only more recently become a profession. Through their brief historical tour, Cavalier, Hoffman, and Cooper make a persuasive argument for getting involved in citizen science by offering up numerous examples of citizen science that have contributed to important and influential scientific discoveries. They further elaborate on how citizen science can transform science and society, especially in the digital age. The internet and smartphones that have made the opportunities to get involved both easier and more numerous.

The Field Guide to Citizen Science

The implicit encouragement to partake in citizen science is made more explicit in the next chapter aptly titled “YES, You Can Be a Citizen Scientist.” The chapter is designed to alleviate the doubts of those who question their ability to participate in science by discussing the crucial relationships between professional and citizen scientists in executing scientific projects. In addition to explaining what citizen scientists can contribute to science that falls outside the purview of professional scientists, the authors also describe a number of methods that professional scientists use to validate citizen science data. This is to say: individuals need not fear hurting research outcomes with their involvement, because training protocols and quality control mechanisms are a regular part of citizen science projects. Importantly, the authors link citizen science and democracy, pointing out that the kind of crowdsourced power – found in both votes and the aggregate data contributed by citizen scientists – has the potential to change the world.

“Prepare to Take the Pulse of the Planet” marks the last instructive chapter of the book and offers up advice for being a successful citizen scientist. The focus is on finding the right citizen science project for you to participate in, which includes consideration of your interests, the time investment required, your abilities, and your expectations for how data will be used and research results communicated. Citizen science projects should be mutually beneficial for project coordinators and citizen scientists, as the authors note: “If you are going to invest time and energy into a citizen science project you should do everything possible to get the most out of it” (33). The authors also provide tips and guidance on being an effective citizen scientist when involved in a project.

Finding the right project

After the first three tutorial-like chapters, the field guide becomes encyclopedic. “Citizen Science Projects to do Online in Your Home, or in Nature,” thematically arranges a catalogue of citizen science projects. For example, those looking to get involved from the comfort of their armchair would check out the “online” section of this chapter; these projects only require an internet connection and the use of a computer. One such project is Flu Near You, which requires only that you answer brief survey questions each week to help epidemiologists predict and prevent the next flu pandemic. For projects “at home,” citizen scientists could expect more hands-on contributions, like taking photos of pumpkins and their insects and microbes for The Great Pumpkin Project or collecting a soil sample from your backyard to assist in the discovery of life-saving antibiotics for What’s in Your Backyard?.

Citizen scientists interested in projects that get them outside of their own backyard can check out the “Near Water,” “At Night,” and “Out and About in Your Community” sections, where they’ll find projects like Marine Debris Tracker, ZomBee Watch, and The Lost Ladybug Project. And finally, the “Chance Participation” section is one that you need to be in the right place at the right time for; like the Dragonfly Swarm Project that asks users to report on dragonfly swarm behavior if they spot it. Particularly useful is that for every project entry, a description of the project is given, along with relevant details under subheadings labelled: Location, Website, Goal, Task, Outcomes, and Why we like this, which gives readers a quick glimpse of the project to help them evaluate if they’d like to participate.

The chapter titled “Citizen Science in Schools, Libraries, and the Community” targets educators and librarians, explaining how citizen science can be built into curricula and introduced to public audiences. Additional project entries in this chapter are tailored to this audience, like the Ant Picnic project that would see students create different ant baits and record how many ants the bait attracts to assist scientists in learning about the global food preferences of ants. The use of SciStarter is particularly noteworthy here, since registered users can earn credit for their contributions to affiliate projects. For students needing evidence of their participation in citizen science for homework, volunteer hours, or extracurricular activities, SciStarter provides an easy-to-use tool. In addition, there’s a section in this chapter titled “At Science Centers Museums, and Aquariums” that would be of interest to all citizen scientists, as it provides examples of public programming that citizens scientists can contribute to should they visit different institutions.

“A Year of Citizen Science” marks the concluding chapter and assembles a calendar that considers citizen science projects in context of holidays, current events, and seasons. For example, you might mark April in your calendar for the launch of the world’s largest citizen science initiative, Earth Challenge 2020, while for December you might plan to spend your holidays participating in the Christmas Bird Count. The point is, it’s always a good time to participate in citizen science!

Tucked behind this chapter is a bonus chapter containing “Resources and References.” With lists of resources to support educators, different kinds of citizen science programming ideas, and further reading about citizen science, this section equips readers with tools for taking the next step in their citizen science journey.

Catching the citizen science bug

This book is infectious in the best way possible. In a world that often feels like it is spinning out of control, where your actions can appear insignificant and change seems out-of-reach, this book gives you hope, a sense of possibility, and perhaps even a purpose. It provides evidence that the actions of citizen scientists make a difference and invites you to do the same. Indeed, the book is punctuated with success stories of citizen scientists, explaining how they got involved and the positive differences that these citizens have made. And who knows, you might soon find that you have your own citizen science story to tell, and perhaps it will begin with picking up The Field Guide to Citizen Science. And for those of you already acquainted with citizen science, you might think about gifting this guide to a neighbour, your child’s teacher, a local librarian, or anyone else who you would like to invite into the rewarding world of citizen science.

This review is part of an ongoing series of book reviews written by members of Dr. Ashley Rose Mehlenbacher’s research team in partnership with SciStarter. If you have a recommendation for a book to review, please contact SciStarter Editor Caroline Nickerson at CarolineN@SciStarter.org. This work has been partially supported by the Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science’s Early Research Award program; and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant program. Views expressed are the opinions of the author and not funding agencies.

Want more citizen science? Check out SciStarter’s Project Finder! With 3000+ citizen science projects spanning every field of research, task and age group, there’s something for everyone! You can also read more from the SciStarter Blog hosted by Science Connected.

Devon Moriarty is a PhD Candidate in English Language & Literature, Rhetoric at the University of Waterloo. Her research examines political and science communication in online environments.