Sahithi Pingali, a young scientist, created the WaterInsights™ citizen science project after being featured in the INVENTING TOMORROW documentary.

By Caroline Nickerson

INVENTING TOMORROW, a documentary, follows several young scientists on their journey to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF), a program of Society for Science & the Public. With their projects, these scientists tackle complex environmental issues affecting water, air, and soil quality.

After you watch, you can help one of the teen science stars, Sahithi Pingali, achieve her goal of creating a global platform to share water quality data, so someday all people have clean water in their homes and environments.

First, select the WaterInsights™ project on SciStarter and sign up to test Sahithi’s free, beta water testing kit. She wants to hear your thoughts on how to make it better. Five hundred people who sign up will receive free beta kits, along with instructions on how to test and report water quality data.

Also, consider getting involved in other citizen science projects on SciStarter’s INVENTING TOMORROW page to help scientists keep an eye on air and soil quality. You can complete all three projects to receive a Superstar Citizen Scientist certificate in your SciStarter dashboard.

Did you know that smartphone touchscreens can now detect contaminants in water samples?

Q&A with WaterInsights™ Creators

Want to learn more about the team behind WaterInsights™? After being featured in INVENTING TOMORROW, Sahithi teamed up with Garand Tyson to create the WaterInsights™ project. The app is still in development, and you can take part in this project by signing up on SciStarter.

In a Q&A, Sahithi and Garand shared a little bit about themselves and about their work.

Conversation with Sahithi Pingali

What’s your professional background? I am currently a second-year undergraduate student at Stanford University. I have worked in environmental research and activism, specifically around water pollution, since the age of 15. I’ve collaborated with interdisciplinary stakeholders ranging from scientists to social workers, businessmen, and politicians. I did internships in water research at the Ecological Sciences Center at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore; the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and the Nanotechnology-Enabled Water Treatment group at Arizona State University, Tempe.

Why citizen science? I’m passionate about getting people to engage with environmental issues in their own local area. Environmental issues often feel overwhelming – things like climate change and industrial water pollution seem too large and complicated for one person to make a difference, and it’s hard to know where to start. Citizen science is a great starting point to gain core scientific understanding of a problem, while also making real data contributions, learning environmental stewardship, and learning how you can take action to protect your local environment.

In Bangalore, India, I was inspired by the way that citizens would step up to take responsibility for the lakes that they lived near and work to revive and protect them. However, I was also frustrated by a few things – how most of the action came from a very small number of people (when many more reap the benefits of healthy local water), and how citizens were heavily dependent on a small number of scientific experts. I wanted to help more people understand water pollution issues and get involved in taking hands-on action. I also wanted to make it much easier for citizen activists to generate data about local water bodies so they didn’t have to wait for the limited pool of experts to carry out testing. Citizen science seemed like the perfect way to do both of these things.

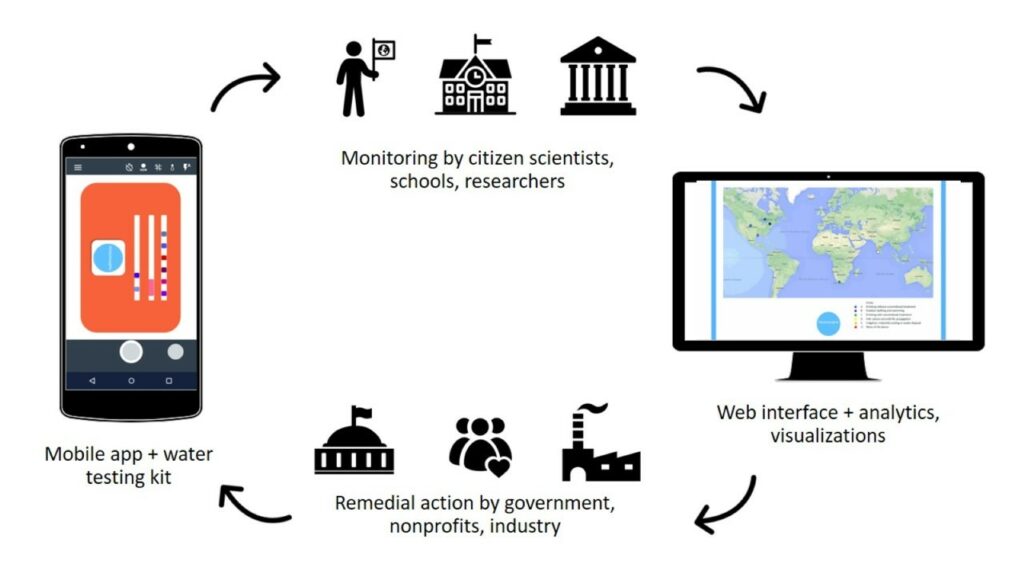

What citizen science project do you represent/run? I represent WaterInsights™, a project that aims to crowdsource water monitoring data at a scale and frequency that has never been seen before. We will make it possible for any citizen to monitor the water in their home or local environment, and then gather that data in a dynamically updated Water Health Map of the World.

How did you start this citizen science project? What made you want to start it? I grew up in Bangalore, India. Bangalore has severe water pollution issues – some lakes in the city are so heavily polluted that they are covered in toxic foam or even catch fire! I was a leader of a club in my high school that worked to raise awareness and funds to help the lakes. As I worked to create awareness materials and talked to various citizen activists, I realized how little scientific data there was about the actual contaminants in the water. Even where data was available, it was buried in jargon-filled scientific reports and was difficult to access. This struck me as a major problem – how could we revive lakes if we didn’t have enough information about the pollution they suffered from? This drove me to create a project that would use citizen science to generate that very information, and also make all the data accessible and easy to understand.

How does someone participate in your project? We’re currently doing our first beta test! Five hundred of the first people to sign up will get a FREE water monitoring kit. Just go to SciStarterand fill out our participation form.

Once we send you our water testing kit, you’ll need a clean container to collect a water sample from a local lake, stream, river, pond, well, or a household tap. Then you can download the WaterInsights™ app to guide you through the stages of water monitoring. You’ll have to dip our test strips into your water sample and take pictures of them through the WaterInsights™ app. Then, the app will upload and analyze those photos to give you your results and help you understand what they mean.

If you can’t download the app, you can still use the instructions in the kit and upload your results from a computer.

How has your project changed over time? For example, has it grown in participants? Have the research goals changed? This project began as a science fair project when I was in 10th grade. Its basic mission then was the same as it is now: to make all the citizens of the world aware of the health of the water in their environment and homes. However, it’s grown and improved a great deal. We’ve developed much more accurate and user-friendly ways to generate water testing data, by improving our app and image analysis methods. We’ve also started to place much more emphasis on the educational aspects of this project. We really want to help people understand what water testing results mean and what they can do to improve the water in their environment.

What’s a memorable anecdote associated with this project? This project was featured in a movie! INVENTING TOMORROW is a movie about teenagers around the world using science and technology to battle local environmental issues, and it follows WaterInsights™ in its early stages when I was working on it as a science fair project.

Where is your project going next? We’re currently running our first beta test where we’re sending out our first five hundred water testing kits (and you should sign up to be a part of it!). We’re going to use the results and feedback from this test to make our system as accurate and user-friendly as possible. Then, we’re going to make test kits available for any citizen scientist to order online. We’re also working to create an educational curriculum to go with the kits, so that students across the world can do this as a classroom activity.

What’s something that you wish everyone knew? I wish everyone knew where their water comes from and where their water goes.

Conversation with Garand Tyson

Tell us about you. How did you get started with this type of work? How would you describe your professional background? Hi! My name’s Garand and I’m a sophomore studying Computer Science at Stanford University with Sahithi. I first started programming in 3rd grade building simple robots out of Legos and programming them to track lines on the floor, do little dances, and complete simple tasks. I fell in love with robotics and went on to compete in middle school science fairs and eventually join a competitive robotics team in high school. While in high school, the robots I built became more complex, and I started to program smartphones to act as the “brains” of the robot and used webcams and other visual sensors to act as the “eyes.” A lot of the algorithms that made my robots “see” in high school are also in the WaterInsights™ app to analyze the test strips using your phone’s camera!

After graduating high school, I worked in a physics lab and wrote Artificial Intelligence programs to help scientists analyze light at the sub-wavelength scale and develop new materials that will be used to create the next generation of touch screens. Currently, I am a software engineering intern at Microsoft, working on Android development and voice assistants.

How does the app work? What makes it different from other citizen science apps? What’s something about it that’s particularly cool — that makes you excited about it? Most citizen science apps are fairly simple. They show users data in a helpful way and allow users to input additional data. WaterInsights™ is different as it automatically collects and analyzes data for you, so you do not have to observe and try to manually interpret the test strip results yourself. It’s not very easy to do this and requires a lot of work in the background (you may notice that the app takes up a lot more space than other citizen science apps).

To analyze the test strips, your phone locates the color squares on the test strip, compares the color to a database, and then tells you the proper reading. While this doesn’t seem too complicated in theory, machine vision tends to be much more complex in practice. What if the test strip is crooked or in the wrong place? What if the card is not perfectly flat when you take a picture? What if it’s sunny outside and there’s sun shining on the test strip? What if it’s cloudy? These are all scenarios that the app has to account for to get an accurate reading.

To get this to work in all conditions, what we have to do is first take the perfect picture, where all the conditions are exactly what we want them to be. To do this, Sahithi spent a lot of time in the lab dipping the test strips in a carefully prepared water sample, aligning the strip just right on the test card, setting up all the lighting, then taking a perfect picture. We then program the phone how to analyze the test strip in this perfect picture.

Whenever you use the app yourself, you don’t spend as much time as Sahithi setting everything up (at least I hope you don’t), so your picture isn’t “perfect.” So the program essentially compares your imperfect picture so Sahithi’s perfect one, and using the power of linear algebra, transforms your picture to be as close to Sahithi’s picture as possible. This means that if it is sunny outside, the program dims the picture to remove the sun. If the test strip is crooked, it turns it so it is straight. After turning your picture into a “perfect” picture, the program then knows how to decipher it and can properly analyze the test strip.

What advice would you give to people who would love to do work similar to what you do, but are perhaps confused or unsure about where to start? Computer Science is one of the most exciting and fastest growing fields today. Once you know how to harness the power of computers, you can really do anything. I’ve made Star Wars video games, robots that play basketball, party planning apps, and scientific discoveries all with programming, and I’m learning something new every day.

All the amazing things you can do with Computer Science is truly inspiring, but it can also be intimidating, especially to people just starting out. My advice to starting out is just to pick a simple project and stick with it. You won’t know how to do everything, but that’s OK. I’ve never started a program that I knew how to write from the beginning. Google is an excellent resource and can answer any question you’ll have, all the way from “How to write a program” to advanced topics in neural nets. The most important thing to do is just to start; everything else will work itself out.

More practically speaking, Scratch is a great learning platform to start programming on. It provides great tutorials to get you started, and while it may look simple, you can use it to build some really cool programs. After using Scratch for a while, Swift is a great first programming language to learn if you use Macs, or Javascript is good if you’re interested in websites.

Finally, you don’t have to take a class to learn how to program. In fact, I think it’s often better to learn on your own just through doing projects for fun. I didn’t take a single programming class until I got to college, but I still was able to learn a lot and build cool and useful applications long before that.

— Caroline Nickerson is the Director of Programs at SciStarter and the Managing Editor of SciStarter’s Syndicated Blog Network. Caroline is a Reilly Environmental Policy Scholar at American University, the Executive Assistant of the UF-VA UNESCO Bioethics Unit, a Vice-President of Scholarships for the DC Gator Club, and the 2019 Cherry Blossom Princess representing the state of Florida.