Pictured in the image above is the Jansky Laboratory, where scientific research is conducted at the Green Bank Observatory, with the Green Bank Telescope (GBT) in the background. The Jansky Lab is named for physicist and telephone engineer Karl Guthe Jansky, who in the 1930s first detected radio waves coming from the center of the Milky Way.

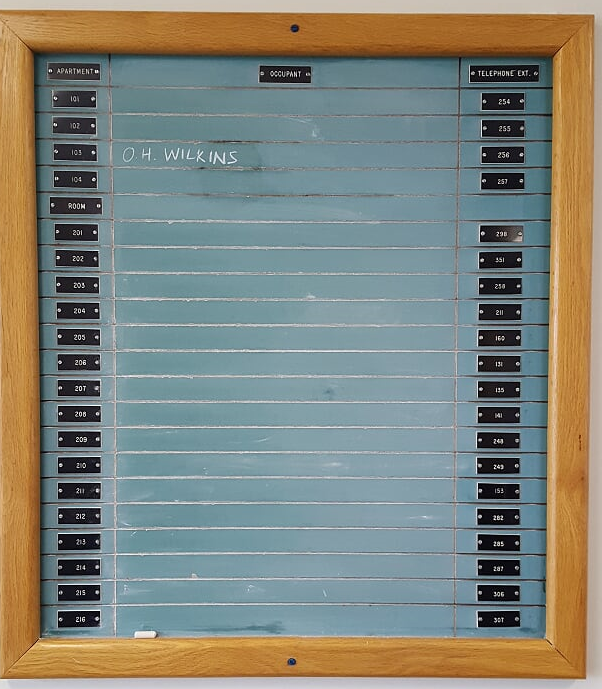

By Olivia Wilkins

Green Bank, West Virginia is known as “America’s Quietest Town”: there is no cell-phone service, and the use of wireless Internet, digital cameras, and even microwaves is heavily restricted. It feels like a snapshot of a time when everybody still had a landline and get-togethers were arranged in advance rather than on a whim with a quick text. For some, Green Bank is a refuge from the waves of ever-advancing technology; for me, it’s a paradise where I can marvel at some of the most remarkable technology in the world: the Green Bank Telescope (GBT).

The Green Bank Telescope is the largest movable object on land. It weighs in at 85 hundred t (17 million lb) and is 148 m (485 ft) high, overtopping the Statue of Liberty. This single-dish radio telescope collects radio waves from distant objects, allowing us to tune in to the invisible universe and piece together the evolution of our solar system and stars, as well as of the wider universe over much of its 13.8-billion-year history. Last October, I was tuning in to that invisible universe during my two-week visit to the Green Bank Observatory. (This is not your amateur telescope–you can read more about those here.)

My lodging: missing the simple things

The folks at the observatory put me up in one of the downstairs apartments in a rather dated on-site residence hall, across the road from the research building. Unlike the dorm-style rooms upstairs, the apartments, which are reserved for longer-term visitors, have a separate bedroom (with both a queen-size bed and a twin-size bed), a living room, a bathroom, and a kitchen, and so they are perfect for small families like mine.

Straddling Virginia and West Virginia, the National Radio Quiet Zone (NRQZ) was established in 1958 by the federal government in part to protect future radio astronomy efforts from the anticipated boom in sources of radio frequency interference, or RFI. I’ve been to the NRQZ several times before, so powering down my cell phone during my recent observing run wasn’t a problem. But as much as I love Green Bank, staying at the observatory there does pose other challenges.

On several occasions, different members of the observatory team insisted that, contrary to popular belief, it was not their cell phone they missed most as Green Bank residents but the microwave oven. Thinking back to my summer visit as an undergraduate research student and, more recently, a visiting scientist, I fully understand this longing. Heating up water in a microwave for a cup of hot tea or cocoa on a chilly evening is so much more convenient than boiling it in a stovetop kettle, just as pre-popped popcorn on a movie night isn’t as satisfying as the microwavable kind.

I know of two microwaves on the observatory site: one in the control room and one in the upstairs kitchen in the residence hall. Mind you, these are no ordinary microwaves. Rather, they have been tampered with by the observatory engineers and stuffed into Faraday cages, that is, metal boxes lined with copper that are able to contain electromagnetic radiation of longer wavelengths, like those emitted by microwave ovens. These special microwaves will run only when the door to their cage is tightly sealed with a heavy metal latch, and because Faraday cages prevent microwave radiation from escaping, the actual cook time is much shorter than that recommended on food packaging.

Tuning in

The observations I was to carry out required only about six hours of GBT time. Staying in Green Bank for two weeks was more of a precaution against the weather, as my work requires conducting observations at high frequencies, which are quite sensitive to variables like temperature, atmospheric water, and wind. My chance for a relatively dry and still night with stable temperature could come only once every few days. Fortunately, I got my chance already on the third night of my visit and was able to use the rest of my stay to consult with the scientists on staff as I looked through my data.

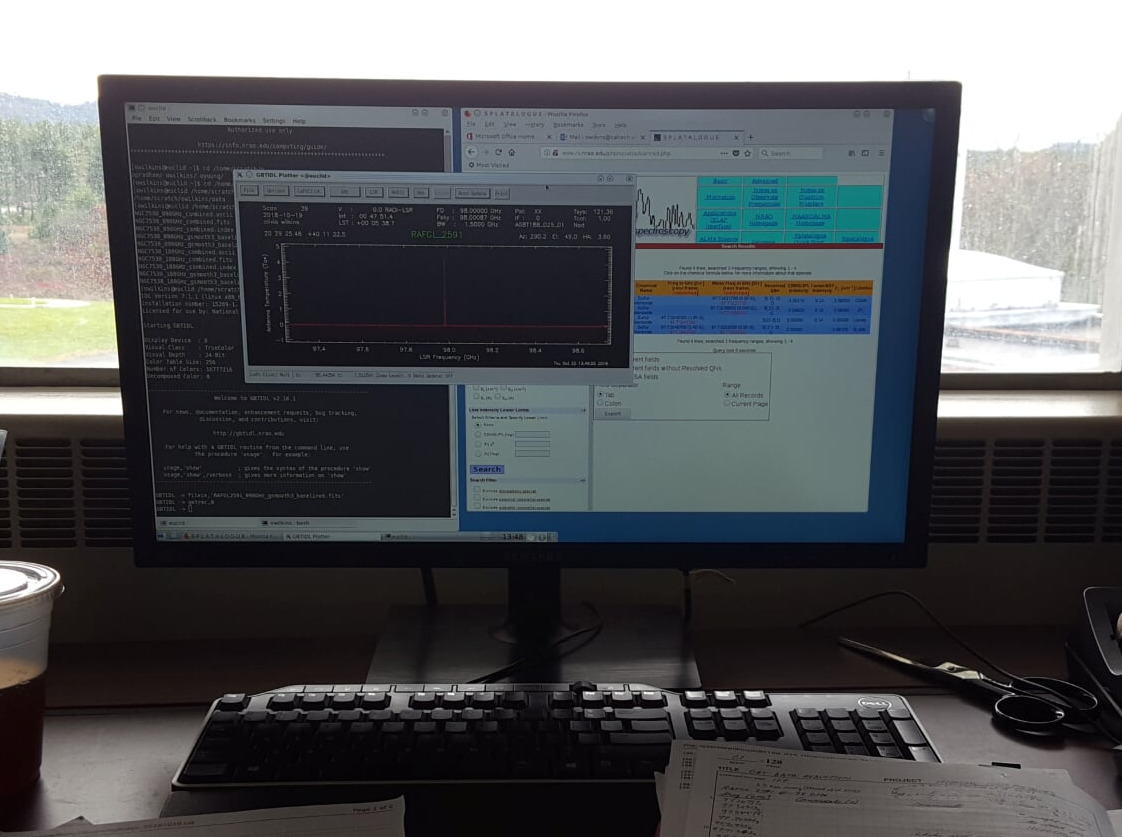

On the night of my observations, I arrived at the telescope control room at 9:45 p.m., about half an hour before my observations were to begin, to meet with my “project friend” (a staff member assigned to help me with my observations) and a resident high-frequency expert. Waiting anxiously as the previous observation run was being remotely wrapped up, I logged into a computer and executed the commands to pull up the appropriate software.

At 10:15 p.m., I got the go-ahead from the telescope operator and started up the receiving instrument for high-frequency studies, only to encounter a “fatal” error. As with any piece of sophisticated technology, the error was fixed with a complicated solution: I turned the receiver off and back on again. Once it was humming along, I initiated a code prompting a sequence to make the surface of the GBT dish as smooth as possible, which increased my ability to receive data with high levels of sensitivity and little radio noise.

Around 11:00 p.m., I started observing two protostars, or collapsing clumps of dust and gas on the verge of star birth. I waited patiently as the data streamed in, occasionally making sure everything was running smoothly. Just minutes before 4:30 a.m., after over six hours of executing various computer codes to control where the telescope pointed and what frequencies of radio emission it collected, I received my final data.

I hung around for another 45 minutes while the next observers remotely checked the surface of the GBT, and I was elated to find that the surface had remained constant throughout my observations, which meant that they were about as sensitive as they could be to the faint signals I was trying to pick up. At around 5:15 a.m., when the morning was dark and still, I trudged across frosty grass back to the residence hall and took a nap before my two-year-old insisted I wake up and join him for breakfast.

Trudging on

The last 11 days of my visit became exceedingly difficult, mostly due to car issues. The morning after my observations, my family and I set off to Snowshoe, a ski-resort village about a 30-minute drive from Green Bank. On our way there, our car began acting funny, sounding more like a 40-year-old pick-up truck, not a 13-year-old SUV. Despite that, we enjoyed the landscape, as fall turned the green and blue mountains surrounding Green Bank amber.

Over the next few days, our car was in a limp mode, at the worst of times struggling to go more than 10 mph. This was problematic for two reasons. First, in his song “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” John Denver doesn’t refer to West Virginia as “mountain mama” for nothing. At the end of one drive, the car didn’t have enough power, and my husband had to push it up the last hill before the entrance to the observatory. Second, being in the NRQZ meant that if we broke down, we wouldn’t be able to call anyone unless we stopped near someone’s house or by the occasional pay phone.

Turns out the catalytic converter had gone out and taken the muffler with it. Fortunately, there is a mechanic several miles from the Green Bank Telescope, and the observatory staff members were exceptionally helpful in giving me rides to the store to pick up milk for my son or to the garage to drop off and pick up the car.

When I wasn’t sorting out car trouble, I was working on my data with the help of the scientific staff on site. We concluded that the signals I had hoped to catch were most likely too faint for the amount of observing time I had. Although disappointing, this realization inspired a cropping of ideas on where to take my research next and how to approach the challenges of observing some of the faintest radio waves from elsewhere in the galaxy.

Once my observations were over, each remaining day went by more quickly and was more difficult than the previous one, with the time to leave Green Bank drawing in closer and closer. Somewhere in between a few dinners and drinks with the observatory staff, I reminisced about my stay there as an undergraduate student and was taken over by a feeling of being at home. Alas, it was time to say goodbye, and I left the paradise of the radio quiet zone at the Green Bank Telescope and went back to admiring radio telescope data instead of the remarkable machine itself.

Until next time, GBT. I can’t wait to tune in to the invisible universe with you again soon.

—Olivia Harper Wilkins investigates the formation of complex organic molecules in the interstellar medium as an astrochemist and doctoral candidate at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Using sensitive radio telescopes, she looks for chemical signatures from the earliest stages of star formation to investigate whether complex organics form on the surfaces of icy dust grains. Olivia earned a B.S. in Chemistry and Mathematics from Dickinson College after which she spent a year as a Fulbright research fellow with the Cologne Laboratory Astrophysics Group in Germany. You can reach her on Twitter, Instagram, and on her website, http://theskyisnotthelimit.org.

All images for this article were contributed by the author.