The Messel Pit Fossil Site near Darmstadt, Germany, was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1995. Where is Messel and what was found?

Gimli: “And they call it a mine. A mine!”

Boromir: “This is no mine, it’s a tomb!”

(Film: Lord of the Rings)

In November 2015, it was my good fortune to tour a special exhibit of never-before-displayed fossils from the shelves of the Hessiches Landesmuseum Darmstadt. The fossils were shown in the Visitor’s Center at the Messel Fossil Pit.

Messel is, indeed, a mine and a tomb, but you won’t find the bridge of Khazad-dûm, a Balrog, or the tomb of Durin like in Tolkien’s Middle Earth Mine of Moria. The story of Messel is every bit as spectacular, though.

Messel Today

The Messel Pit Fossil Site near Darmstadt, Germany, was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1995. According to UNESCO, the site “is the richest site in the world for understanding the living environment of the Eocene, which occurred between 57 million and 36 million years ago.”

Messel is a Lagerstätte. With no direct English equivalent, “Lagerstätte” is a German word adopted into the vocabulary used in paleontology. “Lagerstätte” describes a sedimentary deposit with fossils demonstrating exceptionally good preservation—sometimes including fossilized soft tissues. Messel is especially helpful in providing information on the evolution of mammals. Completely fossilized mammals, including stomach contents, have been found in Messel.

Explosive Beginnings

The Messel site was born in a series of volcanic explosions 47 million years ago. This wasn’t a volcano like the well-known Eyjafjallajökull of Iceland, Kilauea of Hawaii, or Mount St. Helens of Washington State. Those volcanos all have built up volcanic cones above ground in multiple eruptions. A maar volcano, such as the one that formed Messel, erupts underground.

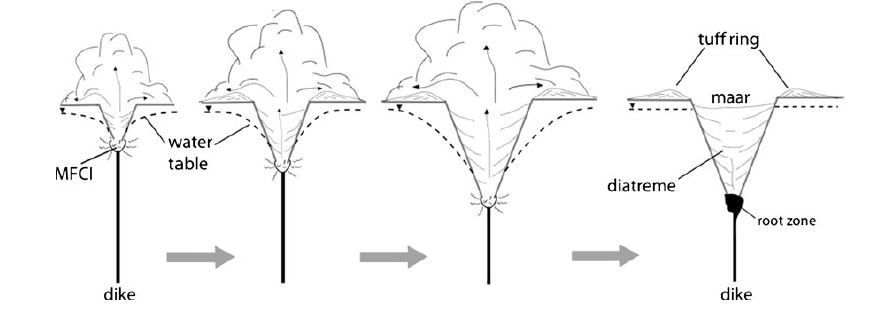

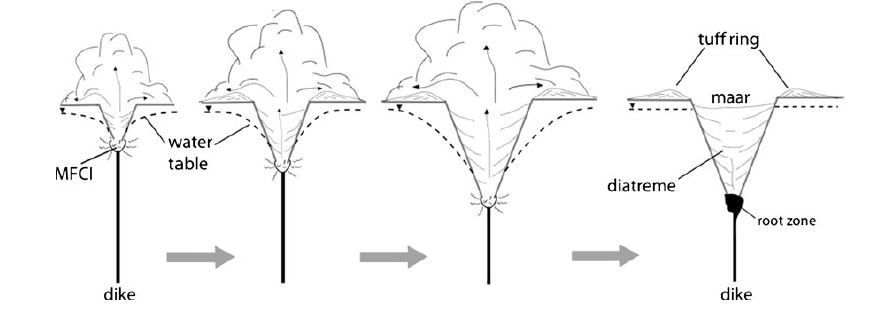

The eruptions are triggered by a column of magma moving towards the surface and encountering groundwater. Water turning to steam under such conditions expands 1,000 times in volume. This sudden expansion produces a steam explosion so violent that it shatters the overlying rocks and ejects them along with steam, ash, and magma. Typically, the deposits travel straight up and fall back on or near the site, producing a ring of deposits around the site and exposing a funnel-shaped mouth. A maar erupts until the available magma is cooled off or the available groundwater is exhausted.

The most recent maars to form are the East and West Ukinrek Maars in the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. They were the result of 10 days of explosive activity in March and April 1977. As is typical of most maars, they have since filled in with groundwater, glacial melt, and rainfall.

Still Waters Run Deep

Maars are generally anywhere from 10 m to 100 m deep and between 200 m and 1,000 m in diameter. The largest maars (300 m deep and 8000 m in diameter) in the world are the Devil Mountain Lakes in the Seward Peninsula, Alaska.

The Messel maar is typical in size: 65 m deep and 800 m in diameter. After its formative eruption, the crater filled in with water, making a lake which many creatures called home. The lake’s depths were low in oxygen, so any animals falling to the bottom did not readily decompose. As they were gradually covered by sediments, the skeletons (and sometimes soft tissues!) were preserved.

What Kind of Fossils?

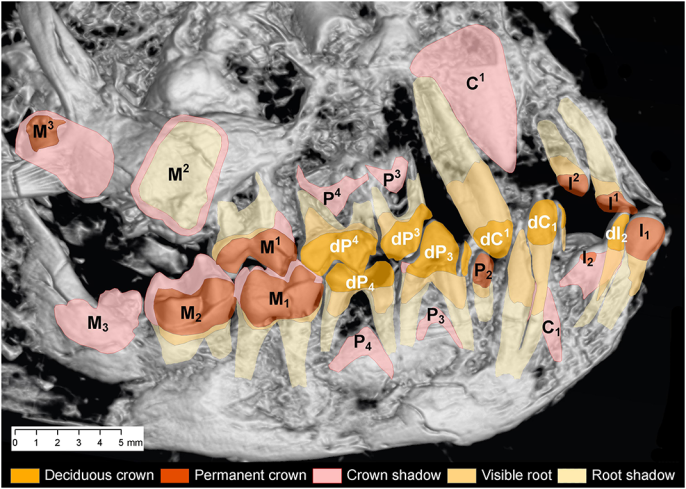

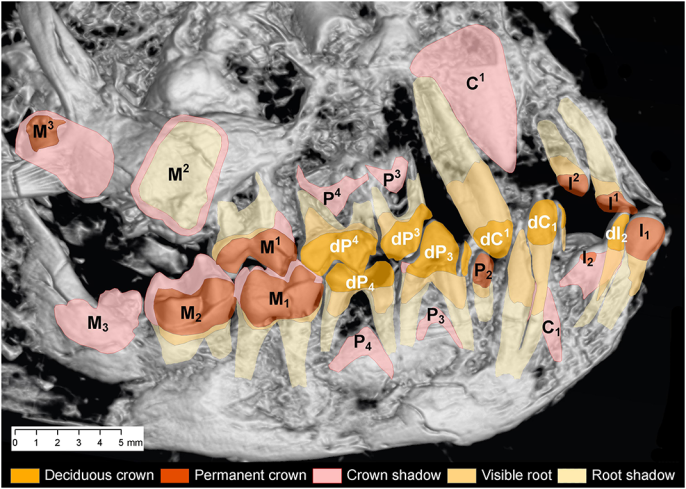

Some of the many species found are frogs, insects, fish, snakes, alligators, crocodiles, turtles, birds, hedgehogs, rodents, bats, early relatives of horses, and primates. The most famous fossil from Messel is Ida, a primate from 47 million years ago (Darwinius masillae). The genus was named for Charles Darwin in honor of his 200th birthday, with the species name from the Latin for the town of Messel).

Messel, Indiana Jones, and Monty Python

Ida’s importance and classification are uncertain. Ida belongs to an extinct form of primates called adapiforms. These primates are usually grouped with the Strepsirrhini, which includes lemurs, aye-ayes, and lorises. The other primate group is the Haplorrhini, which includes tarsiers and simians. The 2009 paper announcing Ida places her in a group representing early Haplorhines, implying that Ida was possibly a transitional form and a distant ancestor of humans. Other scientists have strongly criticized the methodology, pointing out that only 30 traits, instead of the standard 200 to 400 traits, were used in the comparative analysis to determine which family it belonged in.

Ida is also disputed because of the extraordinary publicity concerning its unveiling. The fossil itself was found in 1983. There was a top and bottom half of the fossil available but they were separated. One half arrived in a private museum in Wyoming in 1991. The other half was kept by a private collector in Germany until being sold in 2007 to an international consortium of natural history museums. These museums then had experts work on the scientific description of the fossil for two years.

Because of concerns about how previous finds had been communicated in web blogs, one of the scientists, Jørn Hurum, engaged media specialists and worked with various broadcasters prior to the publication of the paper. His intention was to “take [the] story straight to the masses in a way that would appeal to the average person, especially kids.” Unfortunately, the publicity machine got out of control, and Hurum also made some statements contributing to the situation. Some of his more colorful statements included: “This specimen is like finding the Lost Ark for archeologists” and “It is the scientific equivalent of the Holy Grail.” He also compared the fossil to the Mona Lisa as an icon to bring in visitors. Many scientists have expressed concern with the publicity campaign, the exaggerated claims, and the reporting implying Ida was a direct ancestor of humans.

To be fair to the scientists in the original paper, they explicitly said, “We do not interpret Darwinius as anthropoid, but the adapoid primates it represents deserve more careful comparison with higher primates than they have received in the past.”

Regardless of the hype, Ida is undoubtedly an important find even if it should turn out to “only” be an ancestor to lemurs, which is my best understanding of the various scientific positions.

Preparing Messel Fossils

As mentioned in the introduction, Messel was a mine. Oil-bearing shale was mined from the site for oil extraction until it became economically unprofitable in the early 1970s. After the mine closed, politicians wanted to convert the site into a landfill. Residents and scientist protested against the plans. While many fossils were probably lost during the mining operations, it is only because of the mining that fossils were exposed. Fortunately, the significant scientific value of the site—demonstrated through the fossil finds, vocal ongoing protests by residents, and at least one court case led to the landfill plans being dropped, thus preserving the site for future generations.

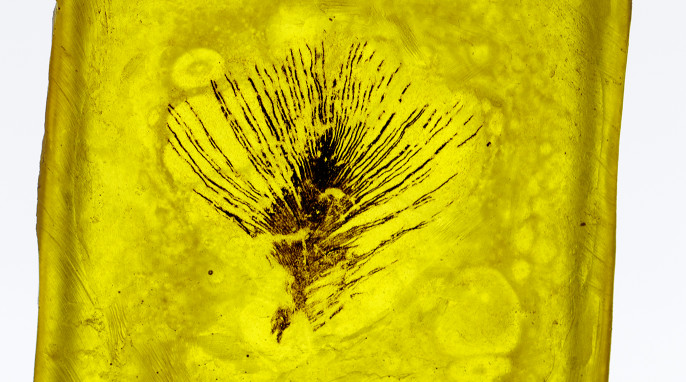

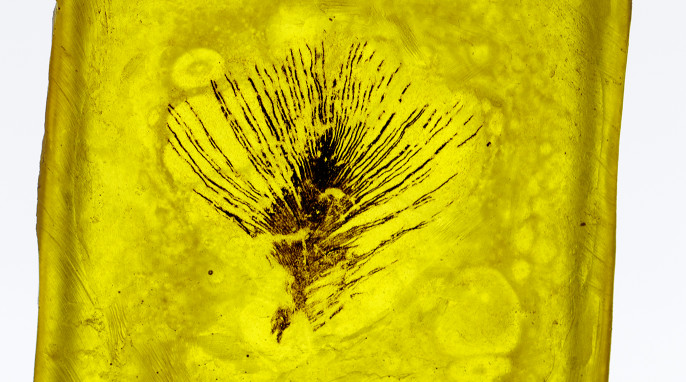

The fossils in the Messel shale are extraordinarily fragile. A special technique called a transfer process is required to prepare these fossils. In many museums, it is common to see entire freestanding skeletons of animals from other fossil sites that were extracted from the rock matrix they were embedded in. Not so with the Messel fossils; they would fall apart if completely extracted. The shale oil in the rock keeps them moist, but when exposed to air, the fossils rapidly dehydrate and crumble away. To prevent this decay, one half of the fossil must be embedded in an epoxy or polyester resin before preparation of the fossil begins.

The fossils from Messel are sometimes exquisitely detailed. Stomach contents, internal organs, skin, hair, feathers, and even the coloration of beetles have been preserved.

If you happen to be in Frankfurt, Germany, the Messel Pit is approximately a 30-minute drive from the International Airport. With luck, you can tour the site with a paleontologist, perhaps see digs in process, and definitely view many fossil exhibits in the Visitor’s Center.

Additional Reading

http://www.grube-messel.de/ (German)

Simulating a Maar (Jessica Ball blog)