What is a biobank? And why do scientists collect human tissue for research? Dr. Cathy Seiler, who manages a biobank, explains.

To understand what biobanks are and why they exist, it is helpful to first understand what type of “currency” is stored in the “banks” and what this “currency” can purchase. The currency in biobanks are biological specimens (sometimes shortened to “biospecimens” or just “specimens”), and these biospecimens are used to “purchase” knowledge through scientific research or preservation.

What is a biobank?

Biospecimens can be any type of biological sample or material. Seed biobanks, such as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, contains tens of thousands of seeds from over 4,000 essential food crops. The purpose of this biobank is to function as a backup for seeds being stored in various countries. If a crop is wiped out because of disease or a zombie apocalypse, these seeds can be “withdrawn” from the biobank and used to grow these crops again.

Shelf Life: 33 Million Things in the Vaults of the American Museum of Natural History

The collection of birds, insects, butterflies, spiders, and other animals and plants stored at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institute is also considered a biorepository. The value of a seed bank is obvious, but what is the value of a collection of dead animals or plants? First, it is interesting for the public to see the diversity of animals and plants found around the world and throughout time—who doesn’t like dinosaurs? But more than that, these collections are also immensely useful to scientists interested in studying the animals themselves and topics including extinction, diversity, and evolution.

Why do biobanks store tissue samples?

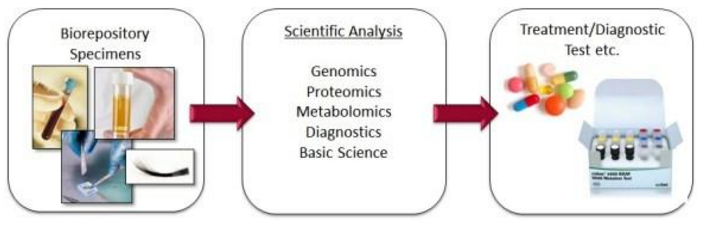

Biobanks that contain human tissue are highly applicable to the study of humans and disease. The biospecimens stored in this type of biobank may include urine, blood, tissue (for example, extra tumor tissue removed during a surgery), feces, cells (for example, cells scraped from the inside of the cheek or skin cells), cerebral spinal fluid, or DNA or RNA isolated from these tissue or fluid samples. The purpose of human tissue repositories is to use these biospecimens to better understand diseases, and to use this understanding to develop molecular diagnostics and treatments.

How is this done? Let’s say scientists are interested in understanding glioblastomas, a type of brain cancer. They would compare glioblastoma tumor tissue that was in excess after surgery or blood samples from glioblastoma patients to tissue or blood samples from patients who do not have that disease, using an “-omic” analysis. By comparing the differences between these two sets of data, they might be able to discover, for example, what types of changes in the DNA cause the disease. Through understanding what causes the disease, they could devise methods to better detect the disease early or to treat the disease in a targeted way.

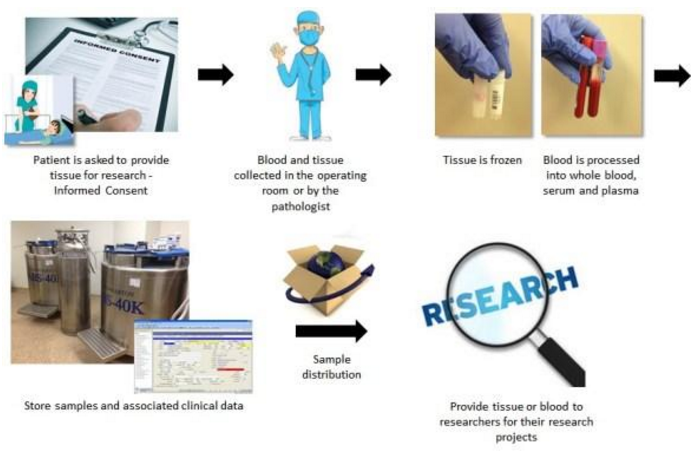

But you may be wondering how it is possible that tissue biorepositories exist at all? It is all because patients have been gracious enough to contribute some tissue, blood, skin, or nails for researchers to use. When collecting samples, the patient always comes first. Therefore, before collecting any tissue for research, the biobanker talks to the patient and explains the purpose for collecting and storing the sample. The biobanker explains any risks and asks for permission through a process called informed consent. If a patient does not consent to donate tissue for research, this does not affect his or her diagnosis or care in any way; it is the patient’s choice. And even if the patient does give permission, but all the tissue ends up being needed for diagnosis, then none is collected for research—again, the patient’s wishes and medical care always come first. If consent is given, the surgeon removes a small piece of tumor tissue during surgery, puts it in a tube, and freezes it quickly at a very low temperature in liquid nitrogen. This piece of tissue, along with a small sample of blood, is then stored in large liquid nitrogen tank freezers until it is requested by a scientist to study that particular type of cancer.

Biorepositories are the custodians of these donations; their purpose is distributing these biospecimens to researchers to study. Thousands, or more likely hundreds of thousands, of studies have relied on biospecimens to better understand diseases or to develop treatments. For example, tissue from melanoma patients was used to identify a mutation found in about 50 percent of these patients. This mutation can be specifically targeted by a drug that significantly improves progression-free survival in patients who typically have a dismal prognosis.

Even more studies are in progress, with the goal of using knowledge gained from these priceless biospecimens to reach the promise of personalized medicine.

The original research paper, “Sustainability in a Hospital-Based Biobank and University-Based DNA Biorepository: Strategic Roadmaps” (Seiler et al., 2015) is published in the journal Biopreservation and Biobanking.

About the Author

Dr. Cathy Seiler is the manager of the Biobank Core Facility at Barrow Neurological Institute and St. Joseph’s Hospital. She received her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology at Boston University, and her PhD at the Watson School of Biological Sciences at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, studying cancer. In her spare time, Cathy is the assistant editor for the ISBER News and writes about science and the life of a scientist on her blog Things I Tell My Mom. She also plays in the handbell choir Campanillas del Sol and enjoys reading, knitting, and spending time with her husband and two dogs in Phoenix, Arizona.

Photo credit: Christian Guthier