Finding Earth-like planets that may someday support life just got easier. Among the billions and billions of stars in the sky, astronomers look for young planets (so-called infant Earths) where life might develop. New research from Cornell University shows where, and when, infant Earths are most likely to be found.

The research was supported by the university’s brand new Institute for Pale Blue Dots, to be inaugurated in May 2015, which is dedicated to the discovery of Earth-like planets.

“The search for new, habitable worlds is one of the most exciting things human beings are doing today and finding infant Earths will add another fascinating piece to the puzzle,” says Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy in Cornell’s College of Arts and Sciences.

A world must be able to hold liquid water on its surface to be considered an Earth-like planet and can only do so if it orbits a star at the distance that astronomers call the Habitable Zone. The Cornell researchers have found that the Habitable Zone of young stars is located further away than previously thought, meaning that there are more young Earth-like planets within the Zone with the potential to support life.

“This increased distance from their stars means these infant planets should be able to be seen early on by the next generation of ground-based telescopes,” says research associate Ramses M. Ramirez. “They are easier to spot when the Habitable Zone is farther out, so we can catch them when their star is really young.”

Kaltenegger and Ramirez give estimates for where habitable infant Earth-like planets may be found, enabling researchers to more easily find young, Earth-like planets. This new information also makes it possible to assess the maximum potential water evaporation for rocky planets that are at equivalent distances to Venus, Earth and Mars from our Sun.

Ramirez and Kaltenegger also found that planets lose the equivalent of several hundred oceans of water during the early period of a solar system’s development, due to a runaway greenhouse effect. But if those same planets end up being in the Habitable Zone at a later stage, when the star is older, they could still become habitable if more water is delivered after the runaway greenhouse effect ends. (For example, we recently reported on a comet that passed very close to Mars and delivered minerals to the Martian atmosphere).

“Our own planet gained additional water after this early runaway phase from a late, heavy bombardment of water-rich asteroids,” says Ramirez. “Planets at a distance corresponding to modern Earth or Venus orbiting these cool stars could be similarly replenished later on.”

The research points to a new era of ‘pale blue dot’ discoveries. “In the search for planets like ours out there, we are certainly in for surprises. That’s what makes this search so exciting,” says Kaltenegger.

The research paper entitled “The Habitable Zones of Pre-Main-Sequence Stars” will be published in the January 1, 2015, issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters. The research into Earth-like planets was supported by the Institute for Pale Blue Dots and by the Simons Foundation.

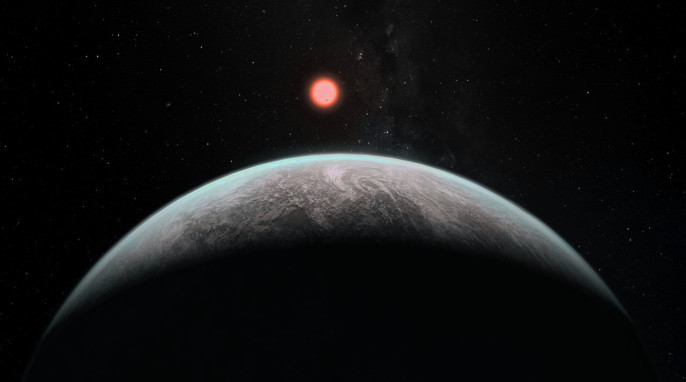

Image: Artist’s impression of how an infant Earth-like planet might look (ESO)