Scientists have used a massive data set of billions of words from actual usage to find that people around the world use more happy words than sad words.

In 1969, two psychologists at the University of Illinois proposed what they called the Pollyanna Hypothesis–the idea that there is a universal human tendency to use positive, happy words more frequently than negative ones. “Humans tend to look on (and talk about) the bright side of life,” they wrote. That speculation has provoked debate ever since.

Now, scientists at the University of Vermont have gathered a data set of billions of words to support the 1960s theory.

People Use More Happy Words Than Sad Words

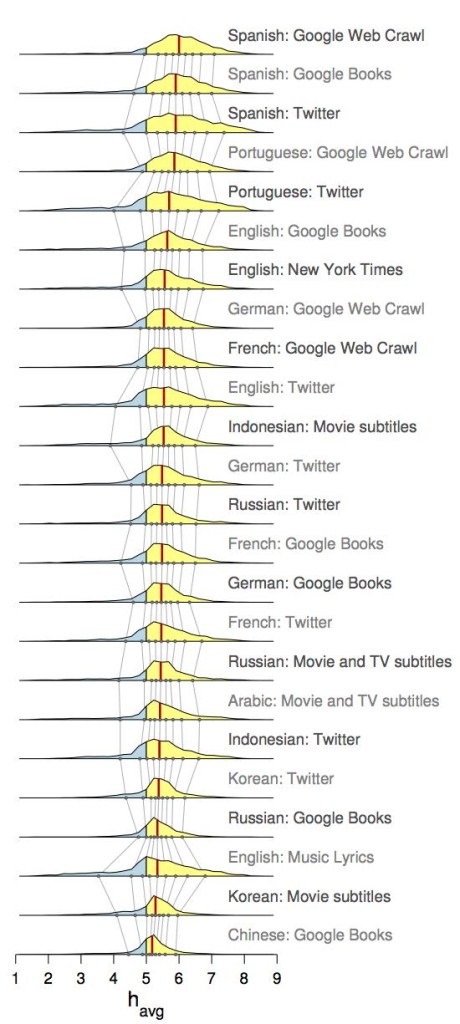

The researchers collected samples of ten languages, including movie subtitles in Arabic, Twitter feeds in Korean, the famously dark literature of Russia, websites in Chinese, music lyrics in English, and even New York Times war articles. “In every source we looked at, people used more positive words than negative ones,” says UVM mathematician Peter Dodds.

What about the torrent of cursing, bigotry, and insults in social media and comment threads? What about reports of crimes and disasters in the news? Negative stories and hateful words often grab our attention, but they are not the majority. This study of individual words suggests that positive social interaction may be built into the fundamental structure of human languages.

Counting “Happy Words”

The researchers gathered billions of words from a smattering of languages using twenty-four types of sources including books, news outlets, social media, websites, television and movie subtitles, and music lyrics. According to UVM mathematician Chris Danforth, roughly one hundred billion words were collected from Twitter alone.

From these sources, the team then identified about ten thousand of the most frequently used words in each of ten languages including English, Spanish, French, German, Brazilian Portuguese, Korean, Chinese (simplified), Russian, Indonesian and Arabic. Next, they paid native speakers to rate all these common words on a nine-point scale and gathered five million individual scores in total. In English, for example, the average score for “laughter” is 8.50, “food” 7.44, “greed” 3.06, and “terrorist” 1.30. Five was designated a ‘neutral score’, and the words with no emotional content, such as “the”, scored in the midrange in each of the languages.

A Google web crawl of Spanish websites showed the language had the highest average word happiness. Words in Chinese books scored the lowest, but across all twenty-four sources, the Chinese vocabulary analyzed tended to skew above the neutral score. The same applied to all the languages studied. And when the team translated words between languages and then back again they found that “the estimated emotional content of words is consistent between languages.”

All of the data showed people using positive, happy words more than neutral or negative words. On average, humans “use more happy words than sad words,” Danforth concludes.

Happy Words, Happy People?

The research team has developed what they call a “hedonometer”–a happiness meter based on real language use. It attempts to trace the global happiness signal from English-language Twitter posts on a near-real-time basis. For example, a drop in happy words was noted on the day of the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, but rebounded over the following three days. In the United States, Vermont currently has the happiest signal, while Louisiana has the saddest. On a more local level, the hedonometer puts Boulder, CO, in the number one spot for happiness and shows Racine, WI, in last place.

The new study is based on the research of Peter Dodds and Chris Danforth and their team in the University of Vermont’s Computational Story Lab. It includes visualization by Andy Reagan, at UVM’s Complex Systems Center, and the technology of Brian Tivnan, Matt McMahon and their team from The MITRE Corporation.

The new study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Support for the study was provided by the National Science Foundation and The Mitre Corporation.

Photo of University of Vermont researchers Peter Dodds and Chris Danforth courtesy of Joshua Brown, UVM