Food waste is a big problem in the United States, where each household discards an average of one third of the food people buy.

By Angie Lo

Have you ever reached for an apple from your fruit basket, only to find out they’ve all gone spotty and bruised? It turns out they might not actually be as bad as we think.

We can sometimes be rather critical of our produce—we often avoid picking oddly-shaped vegetables at the store and toss out fruit from our fridge when we start seeing strange marks on it. In many cases, however, these oddities are no more than visual imperfections that don’t affect the quality or safety (or sometimes even taste) of the food. For instance, slight bruising on an apple is often a natural result of its outer cells reacting to oxygen in the air—the apple may still be perfectly okay to eat.

Throwing out food that’s not actually bad doesn’t just cause us to miss out—it also contributes to the growing problem of food waste in the United States, where each household discards an estimated average of one-third of the food they obtain.

Culturally, why are we so averse to funny-looking fruit? A study from the University of Copenhagen showed that our emotions and attitudes play a strong role in how we perceive food—even overriding what is actually there.

Food waste and false impressions

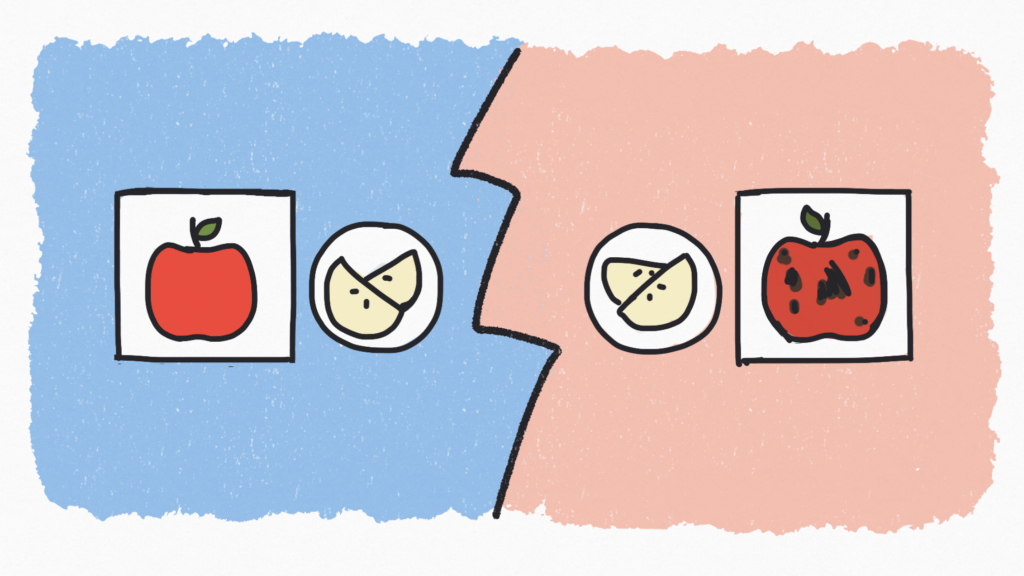

In one of their experiments, researchers prepared special trays of apple slices. They first placed eight pictures atop each tray. One of the pictures was of a nice-looking apple, while the other seven were of apples with visual imperfections—either in shape, color, damage, or a combination of the three.

They then placed a cup of peeled apple slices next to each of the pictures, then gave the tray to participants to sample. The participants thought that each of the cups had apples corresponding to the picture it was beside. In reality, however, the cups all contained slices from the same kind of apple.

The participants then had to rate how much they enjoyed eating the apples from each of the cups, from a scale of 1 (“I absolutely do not like this apple”) to 7 (“I would like this apple very much”). Researchers found that participants, on average, rated the apples they thought had flaws significantly lower than the apples they thought looked perfect—even though there was no real difference between the slices they were eating. This shows how our preconceived attitudes can strongly influence our eating habits and can explain our overly negative and often wasteful actions towards unattractive produce.

The power of knowledge

So how can we tackle this problem? Being more informed about the produce we eat can help us dismantle critical impressions and make better choices. When you see a blemish on your veg, make a habit of looking it up before tossing it—it might turn out those marks or wrinkles aren’t so bad after all. Some sources even provide scientific explanations for why your food looks the way it does—great for getting in some extra learning too. Being informed can influence our shopping habits as well—when we know what it actually is, we can reduce our fears of less-attractive fruit that is still just as tasty and nutritious.

Karin Wendin, one of the study’s researchers, believes in also making this knowledge more accessible. She hopes that grocery stores can play a bigger role in encouraging customers to pick out more imperfect produce, and considers taking advantage of social media as an effective channel of communication. People in science and sustainability are working on increasing accessibility as well. Dana Gunders, former Senior Scientist at the environmental advocacy group NRDC, has also featured on and written articles for major news sites on how to avoid wasting safe food. Research manager and science communicator Rachael Jackson runs a website called Eat or Toss, where she posts explanations and answers readers’ questions about food gone strange. The site also features creative recipes for using up produce scraps and old food, like pickle juice bread and delicious papaya seed dressing.

RELATED: Mushrooms get their moment in the limelight in new research

We can all adopt more practices to combat food waste in general, such as freezing produce and leftovers so they last longer, or placing more perishable foods in a special drawer so they don’t get lost in the back of the fridge. Look up new and imaginative ways to repurpose your leftover ingredients—our partners over at SciStarter suggest using some to make an ant picnic. (You’ll also have the chance to be part of a cool citizen science project at the same time!) By bringing more things from our trash to our tables, we can help bring us closer to having a waste-free future.

This study was published in the journal Food Quality and Preference.

All illustrations by Angie Lo.

References

Bolos, L. A., Lagerkvist, C.-J., Normann, A., & Wendin, K. (2021). In the eye of the beholder: Expected and actual liking for apples with visual imperfections. Food Quality and Preference, 87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104065

Hart, J., & Levin, R. (2016, July 26). Is bruised produce safe to eat? https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/is_bruised_produce_safe_to_eat

Yu, Y., & Jaenicke, E. C. (2020). Estimating food waste as Household production inefficiency. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 102(2), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajae.12036