Ecologists can now forecast bird migrations like meteorologists forecast the weather. But without on-the-ground citizen science observations, it’s hard to tell a songbird from a goose.

SCISTARTER BLOG

For many of us, the sound of fall is defined by honking geese overhead and the calls of familiar songbirds in our yards. Every year, billions of birds, bats and insects take to the air in an ancient migration that leads them from the northern reaches of our continent to more temperate climates in the south.

Scientists have understood the basics of these pilgrimages since at least 1822. That’s when a German hunter killed a stork and was startled to find an African spear lodged in the bird’s neck, providing the first direct evidence of its epic, transcontinental migration. Our understanding of migrations has come a long way since then.

We know where most species spend their winters and summers. And longstanding, on-the-ground observations from birders and researchers have even helped suss out changes over time. But researchers are still trying to answer a surprising number of fundamentals about these aerial movements, like what drives the animals to take flight in the first place.

“The questions people have been asking for a while are ‘What are the drivers of migration and are they predictable?’” says Kyle Horton, an ornithologist at Colorado State University who runs the school’s Aeroeco Lab. “People thought that the winds shift and birds take off — or they don’t take off because the winds are not favorable. Temperature relationships, precipitation relationships, timing through the seasons — we knew the basics of all these things, but we didn’t know if we could put all these things into a framework to create a migration forecast.”

Take Part: Help scientists track migrating birds by joining a citizen science project like eBird, the Christmas Bird Count, iNaturalist or Journey North.

Knowing a Bird From a Raindrop

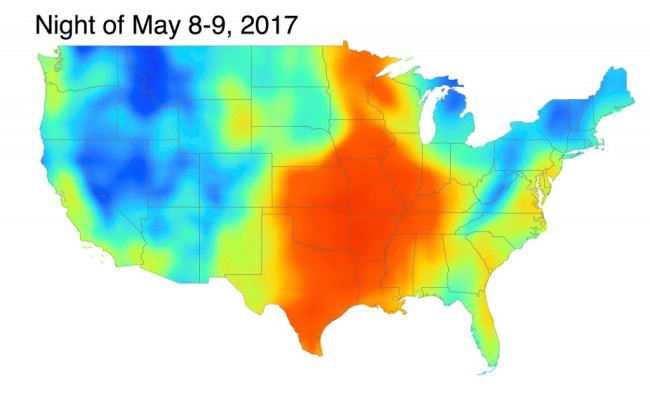

And now a radical new technique is offering up a way to do exactly that — predict annual migrations. In recent years, new tools and initiatives have emerged that give biologists easy access to decades of data from America’s 143 doppler radar stations, which government meteorologists have long used to predict the weather.

A growing group of scientists have learned to study this dataset on grand scales and separate out the signals of flying lifeforms from things like rain, snow, sleet and hail. “To our surprise, we were able to explain migration across the U.S at pretty high levels of accuracy,” Horton says, “probably at levels higher than have ever been seen.”

The technology has revolutionized our understanding of aerial migrations and coined a term for a new field called aeroecology, the study of organisms in the lower atmosphere.

Thanks to aeroecology, migration forecasts are now commonly released through services like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s BirdCast. These forecasts are offering up new discoveries about the science of migrations, and they also help researchers get the word out on big migration nights as animals pass over cities.

“With this new field there are so many possibilities. It’s exciting,” says Jill Nugent, a citizen science expert and dean of science for Southern New Hampshire University’s online STEM programs. “They’re analyzing the movement of birds in the air and then giving folks on the ground advice like ‘turn out your lights because it’s going to be a big migration night’.”

Light pollution leaves birds disoriented and can lead animals away from their migratory paths. As a result, many animals die of exhaustion or in collisions every year. Eventually, researchers hope this information can be used to reach a much larger audience and convince people to turn out their lights.

Help From Citizen Science

Yet there’s still something major missing from these doppler radar datasets. They can’t detect what animals are flying. Radar was designed for weather detection, and while it works great for sensing the size of small objects like raindrops, it has a much harder time with large objects, like birds.

RELATED: The Rise of Drones—and a Way to Monitor Them

“We could create a list of what probable species are up there, but the radars are not going to tell us species identities,” Horton says.

“Without knowing the size of the birds flying, we have to make an assumption,” he adds. “It can greatly skew how many birds are flying in our calculations. For monitoring purposes, it would be great to know just broad taxonomic classifications.”

So, to find out what’s happening in the air, Horton and his colleagues will need citizen scientists who report on the kinds of birds and animals that they’re seeing on the ground in their backyards. It’s not a totally new tactic.

The National Weather Service has long relied on legions of volunteer weather spotters to help validate their predictions and data by reporting back what they see at their homes. In the same way, the field of aeroecology needs an army of citizen scientists to provide ground based observations. If they can marry their models with real-world sightings, they’ll be able to make predictions about what species are flying overhead, and how many birds or bats or insects are flying through.

Give Birdwatching a Try

And to some extent, this data does already exist. Around the country, bird watchers and citizen scientists are using projects like eBird, iNaturalist, Journey North, and more to report their sightings of animals in their homes, neighborhoods and parks.

“There’s this massive wealth of info that we’d like to tie into forecast measurements,” Horton says.

However, Horton adds that these citizen science datasets haven’t yet been integrated into migration forecasts. And there are a few practical issues standing in the way. For one, the scientific field is still small. It needs more research funding and more resources to employ the kinds of graduate students, researchers and faculty who would work on these sorts of problems.

But there are also often gaps within citizen science datasets, and that’s something that volunteers can help fill. For example, for obvious reasons, many birders mainly report sightings from near their homes. But migration forecasts could benefit from having citizen scientists start collecting bird sighting data in areas with relatively few sightings.

“We’re always trying to engage more folks in citizen science data collection,” Horton says. “If you’re not collecting data, give it a try — go out with someone who is an expert bird watcher. If there’s an area that you don’t see eBird observations showing up, sometimes filling those gaps can be critical for modeling efforts.”

You can find more citizen science projects using our Project Finder.

Featured image: A flock of barnacle geese take flight during their fall migration. (Credit: Thermos/Wikimedia Commons)