By Cathy Seiler

January is Cervical Health Awareness Month. What do you know about cervical cancer? Probably the only time you think about your cervix is once a year when you get your Pap test (also known as a Pap smear). But maybe you’re not thinking about it enough. How much do you know about what causes cervical cancer? How much do you know about why you get that annual Pap test? And do you know how—or whether—it works?

[tweetthis]Cervical cancer is the only entirely preventable cancer—via vaccination, screening, and early treatment.[/tweetthis]

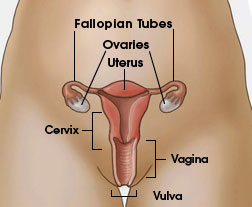

What is cervical cancer and the Pap?

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide and one of the deadliest—even though it is the only cancer that is entirely preventable through vaccination, screening, and early treatment. The Pap, named after its developer, Dr. Georgios Papanikolaou, was designed to detect cervical cancer early, when it is still in a precancerous state. In the test, cells are scraped from the cervix, stained, and analyzed to see if there are any abnormal-looking cells. Although this was a good option during the 1940s for early detection of cervical cancer, in the modern age of molecular biology it is a terrible test. In fact, the Pap may miss disease almost 50 percent of the time because of its subjective interpretation. In fact, one in three cervical cancers occur in women who have had a previously normal Pap result.

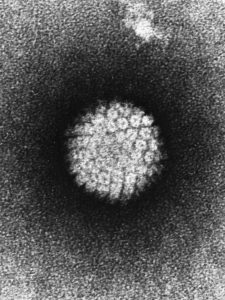

HPV: the virus that causes cervical cancer

Interestingly, more than 99 percent of cervical cancer is caused by infection with a high-risk version of the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV contains genes that act like the gas pedal of a car. But instead of making the car go faster, these oncogenes tell cells to divide more and more, causing cancer—in this case cervical cancer.

There are more than 100 types of HPV, and not all of them are the evil cancer-causing type. Thirteen types of HPV have nasty versions of an oncogene that significantly increases the risk of cervical cancer. So how do you get HPV? It’s actually a very common sexually transmitted disease. About 80 percent of men and women will have an HPV infection in their lifetimes. Thankfully, most infections are cleared by the immune system, so most of us don’t even know that we ever got infected. Unfortunately, in some people the infection persists and may lead to cellular transformation, which can result in cervical cancer years later. Interestingly, these high-risk HPVs not only cause cervical cancer, but they are also responsible for about 70 percent of head and neck cancer. This infection is often acquired through oral sex. In fact, head and neck cancers are expected to surpass cervical cancer by 2020.

New methods to detect and prevent cervical cancer risk

So if the Pap is inadequate, what can be done? In the modern age, when doctors can use specific molecular markers to detect disease, tests have been developed to see if a person is infected with one of these dangerous versions of HPV. If infection with one of the 13 high-risk types is found, doctors and patients know that there is a higher risk of cervical or head and neck cancer.

Screening for HPV is becoming more and more common around the world, and the use of biomarkers to identify which cells are on their way to becoming cancer cells is emerging. In fact, in the United States, if you’re over 30, your doctor may already screen for HPV along with doing the Pap. In countries that can’t afford double testing, screening for HPV is becoming the method of choice because it’s an objective test that looks straight for the cause of cervical cancer. It is also the most sensitive.

You may also be thinking, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could just prevent this HPV infection, using a drug or vaccine or something?” That can be done too. Gardasil, for example, is a vaccine that can be given to both girls and boys to prevent infection from nine types of HPVs. Remember that HPV can also cause head and neck cancer? Unfortunately, there is no good method of screening to identify who is at risk for this type of cancer, because it’s not as easy to access these areas of the body to get a sample to test. Often, during a routine exam, the general practitioner or dentist finds a lesion when it’s already cancer. That’s why it’s so important to vaccinate both girls and boys.

Nobody should have to die from HPV-mediated cancers. So, during Cervical Health Awareness Month, remember to ask your doctor for an HPV test next time you go for an annual exam!

Featured image: A girl receiving a vaccination. Credit: CDC Public Health Image Library.

Hear from a patient about her cervical cancer story.

Learn more about HPV testing in the “Tell your friends and loved ones” video.

—Dr. Cathy Seiler is the manager of the Biobank Core Facility at Barrow Neurological Institute and St. Joseph’s Hospital. She received her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology at Boston University and her PhD at the Watson School of Biological Sciences at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, studying cancer. In her spare time, Cathy is the editor for ISBER News and writes about science and the life of a scientist on her blog Things I Tell My Mom.

GotScience is published by the nonprofit Science Connected. Stories like this one are made possible by donations from readers like you. Please donate today.