Sometimes nature uses physics instead of pigment to create the color blue. Radwanul Hasan Siddique explains how this is accomplished.

By Danielle Bengsch

Pigments are one way to be colorful, but butterflies rely on physics at the nanoscale to create the color blue. The Blue Diadem butterfly, found on the African continent, is roughly the size of a saucer with wings spread. These wings fascinated Radwanul Hasan Siddique of the California Institute of Technology. It wasn’t pigment that turned the butterfly’s wings a radiant cornflower blue, but what was it? He found out and is applying lessons he’s learning from nature’s palette to biomedical devices.

Radwanul Hasan Siddique: I don’t think blue is rare in nature. The sky is blue; so are several butterflies, birds, spiders, even some fruits. Still, this question arises quite often, and the main reason is the rarity of blue pigments in nature. Biological pigments are mainly organic compounds that selectively absorb incoming light and reflect the remaining wavelengths appearing as color. The color blue is shorter in wavelengths that are higher in energy (frequency) compared to green and red. Blue light provides sufficient energy to raise an orbital electron to an excited state and hence forces organic molecules to absorb it. So most of biological pigments absorb blue and therefore appear more green and red in color. If you want to be blue, the simple answer could be that you don’t want to absorb blue.

Siddique: Nature evolved its colors depending on the environment. Usually blue is brighter than any other color in nature. This can be a pro if you want to stand out from others. For example, blue butterflies use their blue to attract mates. A nice example is bright blue Pollia fruit, which comes from Africa and attracts pollinators to carry its seeds around the world.

Siddique: Due to the rarity of blue pigments, nature uses often pure physical phenomena to create blue. This is called structural color. Structural color comes from the light interacting with microstructures and nanostructures on the cell wall or the exoskeleton of the organism it hits. Fundamental optical processes such as reflection, refraction, interference, diffraction, and scattering can become sources of structural colors. Most structural colors are enhanced by combining these optical phenomena. As an engineer and applied physicist, it is particularly intriguing for me to study how nature engineers photonic or optical structures to create blue.

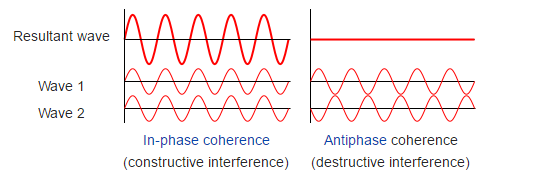

Siddique: The Blue Diadem butterfly has white, blue, and brown-black patches on its wings. Roof-shingle-like scales on its wings create this coloration. A scale usually has two parts: an upper lamina and a thin bottom laminar film. The Blue Diadem’s bottom lamina is perfectly designed to create blue. It’s just the right thickness. The upper, more structured and complex lamina just acts like a translucent window, allowing the blue color to pass through. When light hits a scale, the bottom 200-nm-thin laminar film causes a phase delay of light waves. This phase delay causes superposition of waves, also called constructive interference, which appears as blue (wavelength of 400 nm), and destructive interferences in other visible spectra.

Siddique: The scales are almost 1,000 times smaller than a hair. We used a scanning electron microscope and transmission electron microscope to examine the fine details of the scales in nanometer resolution. Afterward, we used special spectroscopy techniques to analyze the reflected, transmitted, and absorbed light by different scales. Finally, we came up with a theoretical model using the experimental results and explained the Blue Diadem butterfly’s proper physics.

Siddique: Yes, it is. Most blue butterflies use the more complex structures in upper lamina to create a blue coloration. Blue Diadem butterflies use the lower lamina. For example, the famous Morpho butterflies get their blue color from light interacting with the Christmas-tree-like structure of its upper lamina. The bottom lamina doesn’t play any significant role. Usually, if you look at a single Morpho butterfly scale, you will see the blue color quite nicely. In the case of Blue Diadem, you won’t see blue; it looks white. That is what I found fascinating and what started my research.

Siddique: I call what I do bio-inspired nanophotonics. I try to understand the underlying physics of fascinating optical structures found in nature. The next step is to develop affordable nanofabrication techniques to apply these findings, and incorporate them into device-level biomimetic engineering solutions for multifunctional optoelectronic and biomedical applications. For example, my current project is to develop a flexible and convenient monitoring solution for intraocular pressure (IOP) to improve glaucoma management. Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness in 60 million people worldwide. An elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) level has been identified as a major risk factor, and all the glaucoma therapies are aimed at lowering the IOP level. My project focuses on developing a nanophotonic sensor that’s able to detect IOP, performs long-term, and is biocompatible. As my sensor needs to be efficient at various dimensions, I am letting myself be inspired by biological photonic structures that nature uses to optimize itself for different functionalities in the best possible manner.

More about Structural Blues in Nature

Peacocks are known for their bright colors, but those bright colors aren’t a result of pigmentation. It’s called structural coloration. Learn more about Structural Coloration in Bird Feathers.

Curious about how butterflies find food? Check out Picky Eating and Brain Evolution in Butterflies.

Want to read more about blue light versus red light? Read Blue and Red Light: Exploring the Potential.

A version of this article originally appeared on ResearchGate.

Featured image: Blue diadem butterfly, Hypolimnas salmacis. Credit: Bernard Dupont.

Morpho butterfly photo courtesy of Kevin Walsh.