Women in STEM: You Don’t Look Like a Scientist

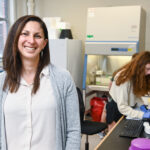

There are many women in STEM professions, yet research shows women who look feminine are STILL perceived as less likely to be scientists. What is being done to overcome this stereotype?

Women in STEM fields have plenty of anecdotal evidence that looking feminine and “looking like a scientist” at times seem mutually exclusive. They’ve revealed their professions at parties to be met with surprise, been asked where the professor is in their own university offices, thought maybe they shouldn’t wear a dress to that conference. Now there’s scientific evidence as well. A paper in the journal Sex Roles reveals that people viewing photos of real researchers are more likely to associate women with non-science occupations if they appear more feminine. Lead author Sarah Banchefsky of the University of Colorado Boulder tells us more.

GET TO KNOW A SCIENTIST: ASTROPHYSICIST DR. MELINDA SOARES-FURTADO

ResearchGate: What motivated you to conduct this study?

Sarah Banchefsky: There is a lot of anecdotal and qualitative work out there showing that women in STEM feel pressure or have been explicitly told to stop wearing make-up, bright colors, and dresses—basically, to assimilate—if they want to be taken seriously in their careers. One study found that the majority of men and women in STEM report that the tension between femininity and science is a serious problem for women in the field.

That said, we wanted to perform a rigorous experimental study to see whether it was really the case that feminine female scientists (but not feminine male scientists) are viewed as less likely to be scientists. This phenomenon had not been scientifically established. A big plus of our studies is that they ruled out the possibility of actual differences in scientific potential of the people being judged—all targets were all qualified, top scientists, so it’s clearly not that the feminine women just aren’t as scientifically capable. We also instantiated femininity in a compellingly modest way: through naturalistic variations in facial appearance—not, for example, by presenting them in high-heels or with obvious make-up or hairstyling. This means this finding likely generalizes to everyone, not just hyper-feminine women, but those who are very subtly and naturalistically more feminine.

RELATED: WHAT DOES A MARINE BIOLOGIST DO?

RG: Can you briefly describe the design of your study?

Banchefsky: In the first study, each participant evaluated 80 photographs (40 men, 40 women) of real scientists at top universities in the United States. Participants were not aware of this, and instead thought they were doing a study on the accuracy of first impressions. They rated various aspects of each person’s appearance, including masculinity-feminininty, attractiveness, and also how likely each person was to be a scientist or an early childhood educator. The second study was similar, but made several design alterations to strengthen our conclusions. First, we removed all appearance ratings so participants were not explicitly asked to consider masculinity-femininity. Thus, to the extent we saw career judgments in in the second study relate to masculinity-femininity ratings made in the first, this indicates that people were using the same appearance cue to make career judgments (femininity) without being asked to consider the target’s appearance. We also added an additional career option, journalist, to ensure participants didn’t think, “well I said they were likely to be a scientist, so I’d better say they’re unlikely to be an early childhood educator”. Finally, we presented faces either blocked by gender, or intermixed randomly by gender. To still see the same effects when faces are presented intermixed by gender means the impact of feminine appearance on career judgments is strong enough to influence judgments even when the most obvious difference between the faces—their gender—is being highlighted.

RELATED: Girl Scouts of Southwest Indiana Citizen Science

RELATED: WANT TO BE A FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGIST?

RG: What were your results?

Banchefsky: Women who looked more feminine were judged as less likely to be scientists, and more likely to be early childhood educators and journalists. In contrast, masculine-feminine appearance had no influence on career judgments made about men. For both men and women, attractiveness predicted being viewed as less likely to be a scientist, and more likely to be an early childhood educator or journalist.

Interestingly, for women, attractiveness and femininity are very strongly correlated, whereas for men, attractiveness and masculinity are only modestly correlated. What we think is important about gendered-appearance being used as a cue for a woman’s career (but not a man’s) is that feminine appearance is linked to gender identity and to other expressions of femininity. Whereas attractive appearance is not clearly linked to other behaviors and attitudes; to downplay femininity means not only to change one’s appearance, but to potentially alter one’s stereotypically feminine behaviors and attitudes as well.

READ MORE: All of Us: A Lack of Diversity in Medicine

RG: I’m sure few female scientists are surprised by these results. Why is it important to have an effect many recognize through personal experience confirmed by research?

Banchefsky: I think empirical validation of intuitive results is important. Personal experiences are a compelling and meaningful starting point, but they are not as convincing and can easily be shot down or explained away. Some will say the number of examples is too small; others may believe that the phenomenon happens but only under specific circumstances—only certain individuals express this bias, or it only happens when the woman is super feminine (e.g., high heels, pink dress). Without scientific studies, there is no way to refute these critiques. Our studies found that most people showed this tendency—regardless of demographic characteristics such as gender, education, or age, and that it emerged even when the targets are naturalistically more or less feminine.

RG: What are the real-life implications of this phenomenon for women in STEM professions?

Banchefsky: For women, this tension between femininity and science likely contributes to a sense that they cannot be both good scientists and feminine women simultaneously. This can lead to a struggle to juggle or manage identities as a scientist and a woman. For example, women may feel pressure to downplay aspects of their female identity in order to be taken seriously as scientists, or to downplay their scientific identity to be taken seriously women—there is some work showing that being primed with romantic goals does diminish women’s interest in science. It suggests that women in science may deal with regular encounters in which people directly or indirectly question their position—telling them they don’t look like scientists or mistaking them for a secretary. Unfortunately, some research shows that tension between femininity and STEM leads some women in STEM to distance themselves from other women in the field. Ultimately, if women do in fact downplay their femininity and assimilate to masculine norms, the masculine status quo is maintained.

On the other side, it is likely that this tension between femininity and science goes beyond simply viewing feminine women as less likely to be scientists; perceivers may also view feminine women as less competent scientists, or less hirable, or less fundable. We are currently analyzing data examining whether feminine women are in fact viewed as less competent scientists.

RG: Did your results vary based on the gender of the person assessing the photos?

Banchefsky: The same pattern of results was highly significant within both men and women, but there was evidence in the second study that women were even more likely than men to use a woman’s femininity as a cue about a woman’s likelihood of being a scientist. Because we only found this result in one of the two studies however, we believe it should be interpreted with caution.

RG: What can be done to counter this stereotype?

Banchefsky: I think we need to spread and share examples of the broad variety of women in STEM. Efforts need to be made to broaden and diversify media depictions and actual representation of men and women who challenge STEM stereotypes. We need to help people see that anyone can be a scientist. The #iLookLikeAnEngineer hashtag is a great example of how people in engineering are celebrating that there is no one type of engineer. This hashtag went viral after Isis Wenger, a female engineer who was featured in her company’s advertisement, had her status as a programmer questioned online because she was “too pretty” to possibly be an engineer. In response, she posted her photo with the hashtag and encouraged others to do the same. The hashtag is now being used in campaigns to broaden everyone’s idea of what an engineer can look like.