Is it time to strengthen the endangered species act? Species are disappearing at a rapid pace, and the ESA is finding it hard to keep up.

Have you ever heard of the Ōlulu plant? What about the vernal pool tadpole shrimp or Fender’s blue butterfly? These are the lesser known species among the almost 1,600 currently listed in the Endangered Species Act (ESA) that require long-term intervention strategies to ensure their survival.

Despite numerous success stories, it is becoming more difficult to recover species. The ESA is beset by persistent and pervasive threats to species, pressures from climate change, uneven distribution of funding among species, and a rapidly growing list of species requiring intervention.

In light of the growing pressures and recent scientific advances, a team of conservation researchers recently released a report outlining six broad strategies that need to be embraced by the ESA to effectively recover listed species.

Unprecedented Pace of Endangered Species Loss

In the last 100 years we human beings have eliminated 10 times more species than have disappeared in the past at the natural background rate. Without conservation, we are at risk of losing precious wildlife and depriving future generations of America’s heritage.

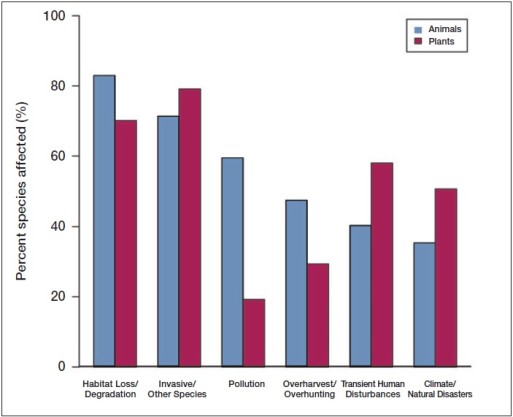

The main driving forces are habitat loss, overexploitation of wildlife for commercial purposes, the introduction of harmful exotic organisms, environmental pollution, and the spread of diseases.

Birth of the Endangered Species Act

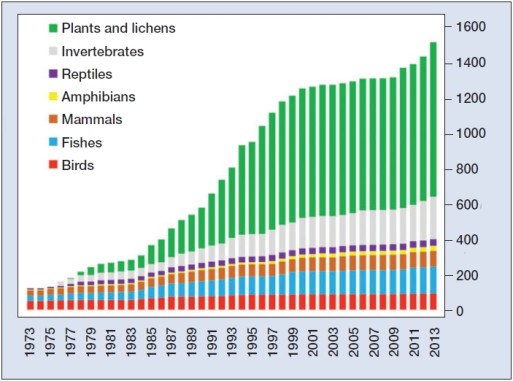

Introduced in 1973, the ESA aims to protect species that are endangered or threatened with extinction.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), together known as the Services, are tasked with identifying and assessing which species to list as endangered and threatened, using scientific studies and data.

The main distinction between endangered and threatened species is time. Endangered species are at immediate risk of extinction, whereas threatened species are at risk within the “foreseeable future.”

Once a listed species has recovered enough to sustain secure populations in the wild in the long term—and can withstand periodic threats such as fire or disease—the Services can delist the species.

Ongoing Challenges

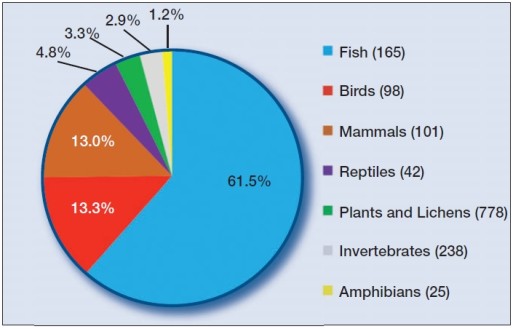

Although the ESA has resurrected hundreds of species from the brink of extinction, critics claim that many species, particularly plants, have been ignored to save a few popular ones—such as the California condor and Chinook salmon—that get the most attention and support.

Most of the government funds received by the FWS are spent to pay staff, fund law enforcement, and have consultations. And even if all the funds were spent strictly on recovery actions, they would still not meet the needs outlined in the recovery plans.

What’s worse, spending has been highly disproportionate: From 1998 to 2012, 80 percent of all the funds went to only 5 percent of the listed species—almost two-thirds of which were fishes. In fact, most of the funds were spent on just 15 species of salmon and sturgeon. And while some species get more than 10 times the funding outlined in their recovery plans, others receive less than 10 percent of their planned funding.

With the growing menace of climate change, many more species need our protection. In 1973, there were only 78 species listed in the ESA; now there are almost 1,600.

Read more: Emperor Penguins Now a Threatened Species

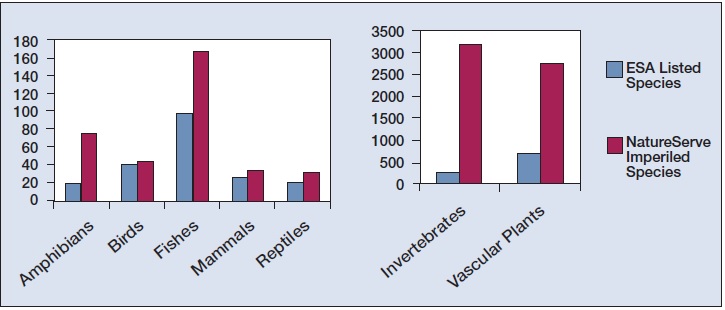

NatureServe is a nonprofit organization that tracks more than 28,000 species in the US. One of the most comprehensive in the nation, it has its own list of endangered species. While the ESA list for birds, mammals, and reptiles match those of NatureServe, there is a massive mismatch for amphibians, fishes, invertebrates, and vascular plants. Also, there is little-known information about the conservation status of a large proportion of invertebrates. Consequently, scientists estimate that at least 10 times more species would probably qualify for protection than are currently listed under the ESA. And only about 2 percent of the species once listed by NatureServe have recovered enough to be delisted.

Because of recent scientific advances, researchers now have access to better data on the status of species and more effective monitoring methods than have been used so far.

Improving Management

Recognizing the need for better management of resources, a team of researchers has proposed six broad strategies for the ESA to follow for effective recovery of endangered and threatened species.

- Establish and consistently apply a system for prioritizing allocation of funds.

This system should consist of criteria devised with the consultation of expert scientists and practitioners. The Services would have to modify budgeting allocations to maximize the recovery of listed species.

- Strengthen partnerships and collaborate with federal agencies, the states, and nongovernmental organizations, as well as develop incentives for landowners.

State wildlife agencies can help to gain the trust and acceptance of hunters, anglers, farmers, landowners, and other groups to support conservation efforts.

Because two-thirds of listed species are found on private lands, the Services need to develop incentives including payments and technical assistance to landowners to encourage them to comply with conservation practices. These incentives need to be evaluated for effectiveness in conservation outcomes and landowner satisfaction.

- Regularly monitor listed species to assess their status and implement adaptive management strategies.

Conducting simple presence or absence surveys of species can help managers identify any trends or changes in distribution of species over time. Researchers can improve monitoring by identifying the minimum amount of information needed to glean the status of a listed species, and to design protocols tailored to a particular species.

Adaptive management involves devising a management strategy, monitoring the outcomes, and adjusting strategies according to the results.

Managers should use data gathered from citizen science projects whereby volunteers from the public monitor the abundance and distribution of a species—this would save resources that can be used for monitoring other species. In 2012, volunteers in South Carolina contributed an estimated $390,000 worth of monitoring of loggerhead sea turtles on beaches.

- Refine recovery criteria to include the best available science.

Using the latest insights, scientists should work with the Services to make recovery criteria—such as abundance, distribution, and mitigation of threats—objective and measurable.

- Implement climate-smart strategies.

Climate-smart strategies include increasing habitat connectivity, reducing impacts from non-climate stressors, assessing species’ vulnerability to climate change, protecting potential future habitats, assisting colonization, and engineering new habitats.

- Evaluate and develop ecosystem-based approaches.

One approach includes using a surrogate species whose requirements represent a large group of listed species. Another approach is to focus on geographical hotspots of listed species with similar threats. The latter has been applied on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, where the FWS grouped 48 species together based on common factors.

Implementing these strategies will ensure the effective recovery of endangered and threatened species.

How You Can Help

If you own land that covers the habitat of a listed species, you can support conservation efforts by complying with the Services in their conservation plans—and live in harmony with other amazing species.

You can also get involved in a variety of citizen science projects.

Reference

Evans et al. (2016). Species recovery in the United States: increasing the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act. Issues in Ecology, 20, 1-29.