The human hand is an evolutionary wonder: 26 percent of the bones in our bodies are in our hands. Now, scientists are coming to better understand the grip and special grasping ability of humans and other primates.

In a new study, a research team found that even the oldest known human ancestors may have had precision gripping skills comparable to modern humans. This includes Australopithecus afarensis, a creature that predates the first known stone tools by about a million years.

Yet there remains uncertainty about the gripping capabilities of early hominins, especially regarding the use of tools. The new study suggests that the early human species Australopithecus afarensis may have had more than enough manual dexterity to grip a stone and use it as a cutting tool. It is possible that our earliest ancestors had other manipulative and tool-related skills that were not preserved in the fossil record.

Grip, Grasp, and Grab

The group that is working to develop a better understanding of how our grip evolved includes Yale robotics engineers Thomas Feix and Aaron Dollar, anthropologist Tracy Kivell of the University of Kent and the Max Planck Institute for Human Anthropology, and primatologist Emmanuelle Pouydebat of the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

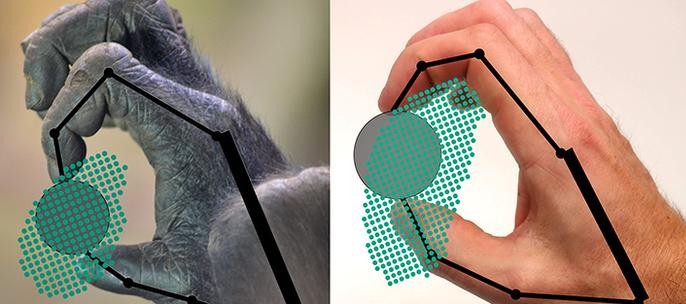

After measuring the bones of living primates and fossils of human ancestors, the team built working models of the thumbs and index fingers. The final model shows how the fingers work during precision grasping and manipulation of small objects.

While other studies of how primates grip have focused on contact between the hand and the object, or on the length of the thumb relative to the fingers, the new study looks at how the thumb and index finger work together to grip small objects. “The model reveals that a long thumb or great joint mobility alone does not necessarily yield good precision manipulation,” says Feix. “Compared to living primates, the human hand has the largest manipulation potential, in particular for small objects.”

These findings appear in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Top Image: This figure shows how a gorilla and a human grip and move an object. The dots indicate positions in which the object can be gripped. (Yale University)