Holes in the sea floor release methane gas. Microorganisms that live near the holes protect our air by eating 75 percent of the methane.

By Kate Stone

Methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, is constantly leaking out of holes on the ocean floor. Now, an international team of scientists have found that these “methane seeps” are home to unique communities of microbes that play an invaluable role in maintaining life on Earth.

Microbes that Eat Methane

Methane seeps in the sea floor release methane into the surrounding water, which is fed on by microorganisms that live on or near these leaks. By consuming the gas, they prevent it from entering our atmosphere.

“Marine environments are a potentially huge source for methane outputs to the atmosphere, but the surrounding microbes keep things in check by eating 75 percent of the methane before it gets to the atmosphere,” says Jennifer Biddle, assistant professor of marine biosciences in the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment. The tiny organisms are an important part of the underwater ecosystem, and help maintain Earth’s climate by controlling greenhouse gas emissions.

More people have traveled into space than into the deep ocean, and Earth’s deep sea canyons are a largely unexplored frontier. Nevertheless, governments and industry are considering mining the deep ocean for minerals, oil, and other valuable deposits, which is worrying scientists. They are concerned about climate change and how the warming of the ocean could affect the deep water and the marine organisms that live there.

The new data about the microbes that dwell in methane seep, and the role they play in maintaining the health of our environment, provides important information about what goes on in the deep sea.

“This collection of data is rare and valuable,” Biddle says. “As the climate warms, changes are bound to occur. Without an initial data set there is no way to measure changes over time.”

The researchers analyzed microbes from 23 methane seeps across the globe — from North Carolina to offshore Antarctica — and compared them to the microbial communities of 54 other seafloor ecosystems.

The researchers theorized that bacteria and archaea would vary by the amount of methane emitted by a given seep, but they discovered that methane secretion is not a factor in what species of microbes are found. Rather, other energy sources from the surrounding environment play a greater role in determining what types of bacteria and microorganisms flourish.

Globally, methane seeps share a core community of methane-eating microbes, but each location has its own unique population. “We found similar groups, but we did not find any one species that was distributed throughout the entire deep sea in all of these environments,” Biddle explains.

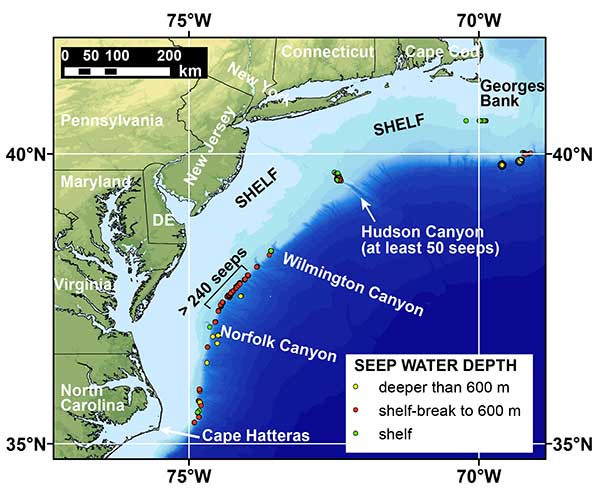

Recent efforts to map the ocean floor by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have led to new discoveries of methane seeps up and down the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic coast of North America.

RELATED: Carbon Isotope Anomaly in the Deep Sea

“It’s an environment where there is a lot of discovery. New seeps are constantly found. It’s intriguing to think we’ve now got reason to keep studying new seeps, determine how they are different and begin asking new questions,” Biddle says.

The team of researchers who worked on this study included members from the HGF MPG Group for Deep Sea Ecology and Technology, Department of Molecular Ecology at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany; and University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany.

The research paper, entitled Global Dispersion and Local Diversification of the Methane Seep Microbiome, is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Featured Image: Numerous distinct methane bubbles emanating from the seafloor at an upper slope (< 500 m water depth) cold seep site, off the coast of Virginia. (Photo courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition)