How can it snow when temperatures are above freezing? Mountain Rain or Snow has the answer — and wants your help studying it.

The SciStarter Blog

A glimpse at the temperature during the next snowfall might surprise you: It may not actually be below freezing outside. Don’t worry, your thermometer isn’t broken, and you didn’t miss a memo about a change in the laws of physics. There’s a straightforward reason why it can snow above 32°F — though it does make it more challenging for meteorologists to forecast whether rain, snow, or something else will be falling from the sky during an upcoming precipitation event.

Before the big reveal, it’s worth mentioning how big of a deal this phenomenon really is, even beyond your snow-day plans. Scientists and water managers across broad geographic regions rely on accurate estimates of precipitation across the winter season. An inch of snow differs a lot from an inch of rain, and correctly identifying a precipitation phase (is it snowing, raining, or mixed?) isn’t as easy as adding a 32°F threshold to weather models and radar algorithms. Especially in the mountains, snowfall affects snowpack water storage, avalanche forecasting, flood predictions, and more. And no matter where you live, city planners want to know how their snowplow and salt truck fleets will be in demand.

Mountain Rain or Snow is a new citizen science project designed to alleviate this challenge for water managers and other hydrologic scientists. The project starts with a simple question: What is falling from the sky right now?

Take Part: Mountain Rain or Snow

When hundreds or thousands of people share their response, the Mountain Rain or Snow team will be able to make better estimates of precipitation phase change and improve the assumptions on which satellite-based and model products make calculations. And you don’t have to be in the mountains to submit a response: Observers from anywhere snowy are invited to upload their observations!

Freezing rain and not-so-freezing snow

Water freezes at or below 32°F, but not instantly. Your water bottle doesn’t freeze solid the second you step outside, nor do your ice cubes melt the second they’re outside the freezer. That’s why regardless of what temperature it is on the ground, the temperature and other conditions higher in the atmosphere have a big impact on whether it’s raining or snowing.

Snow forms in upper layers of the atmosphere, which are generally colder than the boundary layer where we live, work, and play. But snow crystals have to fall through a lot of air before they reach us, and that air may be warmer or colder than where the crystals formed. When snow crystals fall through warmer air, they may melt and turn to rain — but only if it’s warm enough to melt them completely by the time they land.

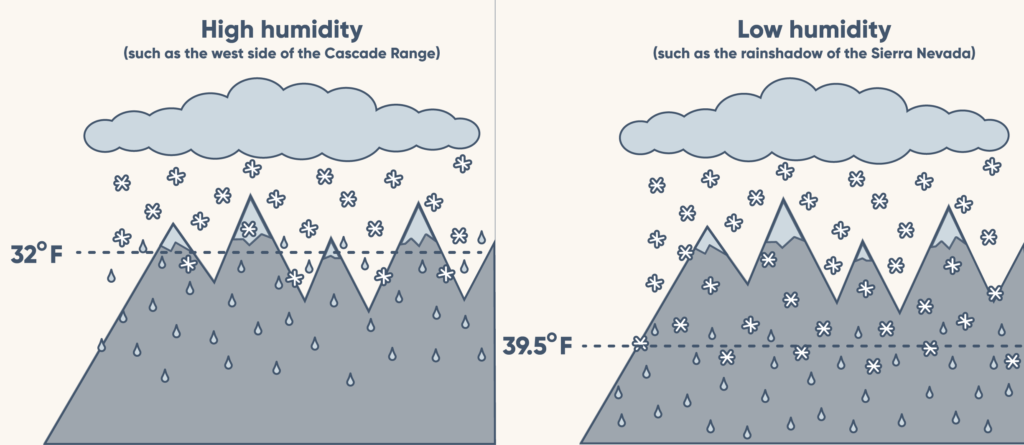

Melt rates depend not just on temperature, but also on the humidity of the air. Think of how your own body responds to heat differently depending on how humid it is. When you sweat, water molecules on your skin transfer heat from your body to the water, which cools you down. When it’s less humid — “a dry heat” — those water molecules can more easily evaporate off your skin, making it much easier to cool off.

Snow crystals also find it easier to keep cool when it’s dry. But instead of evaporation from sweating, the frozen water molecules sublimate (change from a solid to a gas), which gets rid of extra warmth and keeps them from melting. This is easier when humidity is lower because, to get very technical for a moment, the vapor pressure gradient is larger between the crystal and the atmosphere. All this means is snow melts more slowly as it falls in dry climes, which makes it more likely to reach the ground before it turns to rain.

Report rain or snow near you!

Although we know how it works, the challenge of predicting whether it will rain or snow remains for our friends, the water managers. Currently, they rely on satellites to help differentiate between rain and snow, as well as weather models that assume snow transitions to rain at the freezing point. They use these tools because scientists cannot monitor all locations at all times to verify what exactly is falling from the sky at any given moment.

But we can help!

Ground-based observations (what you and I can observe directly) are much better at differentiating snow, rain, and mixed precipitation than atmospheric models are. And the more observations we collect, the more we can improve the models for the future.

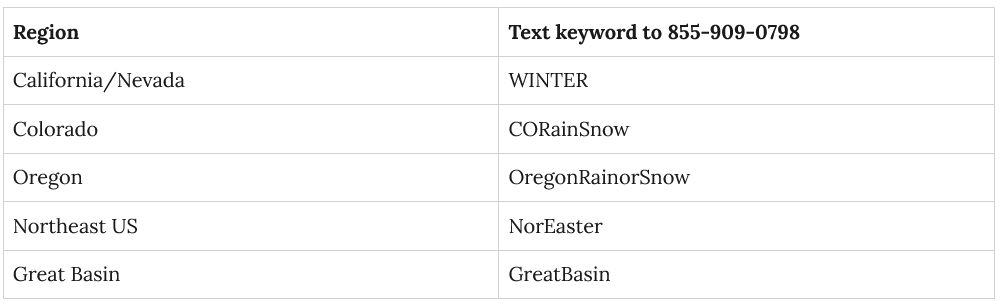

To participate in Mountain Rain or Snow, all you need is a phone or computer and your own two eyes. Our team sends text message alerts to participants when winter storms are approaching, and volunteers can send observations in less than a minute through our web app. Right now, we are focused on five mountain regions, but we gladly accept observations from anywhere in the world.

Getting started is simple. If you are located in or near a region of focus, text your keyword to 855-909-0798. We’ll then send you the directions to get started.

If you are not located in one of these regions, open a browser and type in rainorsnow.app. Sign up, and then share observations whenever it is raining, snowing or a wintry mix.

We share our gratitude with the 800+ citizen scientists who have made over 7,500 observations and counting this season alone! We could not do it without you.

To discover more, visit www.rainorsnow.org. Mountain Rain or Snow is a collaboration between Lynker, Desert Research Institute, and the University of Nevada-Reno. This work is supported by a grant from the NASA Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program.

About the author

Meghan Collins is an Education Program Manager at the Desert Research Institute, and she is a member of the Mountain Rain or Snow team, alongside Keith Jennings (Lynker), Monica Arienzo (DRI), Ben Hatchett (DRI), Anne Nolin (UNR), and Josh Sturvetant (Lynker). She leads the engagement strategy for the project. Meghan uses science communication tools to engage community members in exciting science experiences.