The power of water has long been harnessed by humanity, but another part of the water cycle is being used to turn evaporation into electricity.

Many scientists are experimenting with improved solar cells and biofuels, but Columbia University scientists have a new, noteworthy idea. They have announced the development of a novel device that turns evaporation into electricity. In fact, the small prototype generates enough electricity to power a lightbulb and the rotary engine that drives a miniature car.

Evaporation into Electricity

When evaporation energy is scaled up, the researchers predict it will produce electricity from giant power generators that will float on the surface of bays or reservoirs, or from huge rotating machines (akin to wind turbines) that sit above water.

“Evaporation is a fundamental force of nature,” says Ozgur Sahin, Ph.D., an associate professor of biological sciences and physics at Columbia University. “It’s everywhere, and it’s more powerful than other forces like wind and waves.”

With its current power output, the floating evaporation engine could supply small floating lights or sensors at the ocean floor that monitor the environment, says postdoctoral fellow Xi Chen. It is speculated that an improved version of the new invention could potentially generate more power per unit area than a wind farm.

Building an Artificial Muscle

Last year, Sahin was studying bacterial spores. He found that when spores shrink and swell with changing humidity, they can exert force on other objects. Bacterial spores pack more energy pound for pound than other materials used in engineering for moving objects, he reported in a paper published in Nature Nanotechnology. Now, the research team is building devices that are being powered by a similar type of energy.

To build a floating, piston-driven engine, the researchers first glued spores to both sides of a thin, double-sided plastic tape, much like that found in old cassette tapes. They did the same on the opposite side of the tape, but offset the line so dashes on one side overlapped with gaps on the other.

When dry air shrinks the spores, the tape curves and contracts. If one or both ends of the tape are anchored, the tape tugs on whatever it’s attached to. Conversely, when the air is moist, the tape extends, releasing the force. The result is a new type of artificial muscle that is controlled by changing humidity.

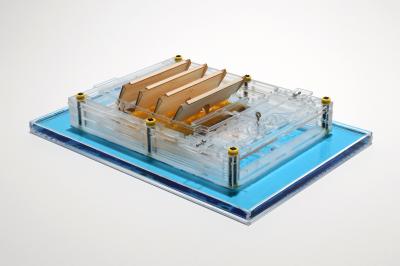

Sahin and Chen then placed dozens of these tapes side by side, creating a stronger artificial muscle that they then placed inside a floating plastic case topped with shutters. Inside the case, evaporating water made the air humid. The humidity caused the muscle to elongate, opening the shutters and allowing the air to dry out. When the humidity escaped, the spores shrunk and the tapes contracted, pulling the shutters closed and allowing humidity to build again. Thus, a self-sustaining cycle of motion was born.

The spore-covered artificial muscles function as an evaporation-driven piston. “When we placed water beneath the device, it suddenly came to life, moving on its own,” Chen says.

Starting Small, Scaling Up

The Columbia team’s other new evaporation-driven engine – the Moisture Mill – contains a plastic wheel with protruding tabs of tape covered on one side with spores. Half of the wheel sits in dry air, causing the tabs to curve, and the other half sits in humid environment where the tabs straighten. As a result, the wheel rotates continuously, acting as a rotary engine.

The researchers next built a small toy car using the Moisture Mill and were successful in getting the car to roll on its own, powered only by evaporation. In the future, Sahin says, it may be possible to design engines that use the mechanical energy stored in spores to propel a full-sized vehicle. Such an engine, if achieved, would require neither fuel to burn nor an electrical battery.

A larger version of the Moisture Mill could also produce electricity. Sahin suggests that a wheel that sits above a large body of water could be turned by evaporating water and generate electricity. This technology would steadily produce as much electricity as a wind turbine, Sahin says.

Work on this project was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, and the David and Lucile Packard Fellows Program. Results were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Video courtesy of Sahin Laboratory, Columbia University. Top photo courtesy of Xi Chen, Columbia University.