About 2.8 million years ago, early humans probably survived on a diet of plants. As the human brain expanded, however, it craved richer nourishment, namely animal fat and meat. Lacking claws and sharp teeth, early humans developed the skills and prehistoric stone tools necessary to hunt large animals and cut the fat and meat from the carcasses.

Recently, this rare fossil shed new light on early human evolution. Long before that, our oldest known primate ancestors lived in trees and may have looked like this. Also, prehistoric human settlements have been found at the bottom of the sea.

Now, evidence of human carnivorous behavior has been found among elephant remains at a Lower Paleolithic site in Revadim, Israel. Archaeologists from Tel Aviv University, the University of Rome, and the University of Negev have analyzed prehistoric stone tools known as “handaxes” and “scrapers,” coated with residue from animals butchered more than 500,000 years ago.

Plenty of bones have been found bearing marks from stone tools, and many of the tools themselves have also been unearthed. Some tools were discovered with the remains of our human ancestors found at the bottom of the sea. However, this new exciting find represents the first scientifically verified direct evidence that Paleolithic stone tools were indeed used to cut up animal carcasses and hides.

“Archaeologists have until now only been able to suggest scenarios about the use and function of such tools. We don’t have a time machine,” says Ran Barkai. “It makes sense that these tools would be used to break down carcasses, but until evidence was uncovered to prove this, it remained a theory.”

Piecing Together the Puzzle of Human Evolution

“There are three parts to this puzzle: the expansion of the human brain, the shift to meat consumption, and the ability to develop sophisticated technology to meet the new biological demands. The invention of stone technology was a major breakthrough in human evolution,” says Ran Barkai. “Fracturing rocks in order to butcher and cut animal meat represents a key biological and cultural milestone.”

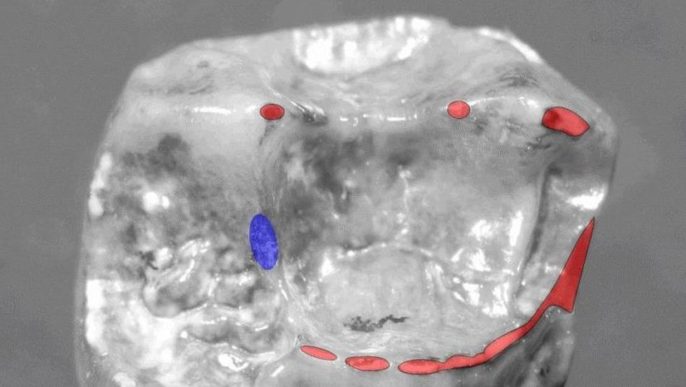

At the Revadim quarry, a wonderfully preserved site a half-million years old, the team of archaeologists found butchered animal remains, including an elephant rib (pictured) that had been neatly cut by a stone tool, alongside flint handaxes and scrapers still coated in animal fat. “It became clear from further analyses that butchering and carcass processing indeed took place at this site,” Barkai says.

Scientists examined the tools with use-wear analysis — examining the surfaces and edges of the tools to determine their function — and the Fourier Transform InfraRed (FTIR) residue analysis, which harnesses infrared to identify signatures of organic compounds. The results enabled the researchers to demonstrate for the first time that our ancient human ancestors used prehistoric stone tools to butcher animals.

Prehistoric Stone Tools, or Swiss Army Knives

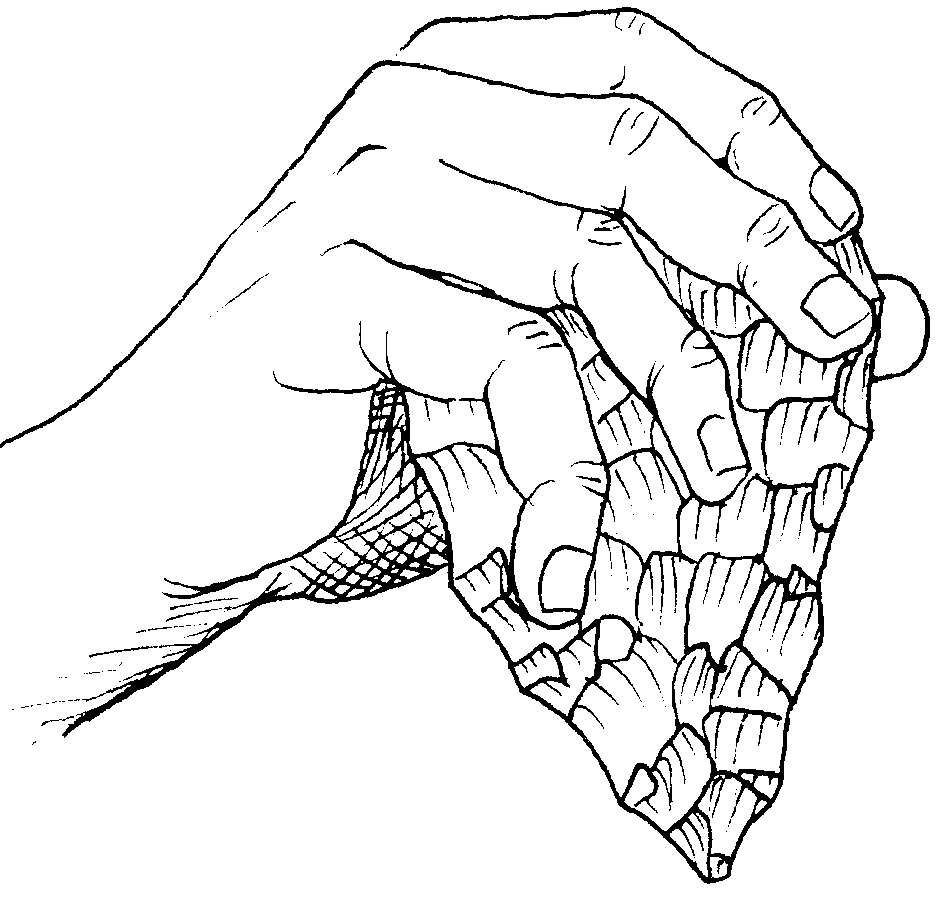

Hand axes and scrapers have been found at prehistoric sites all over the world, and there has been little doubt that they were used for specific purposes. By replicating the flint tools for a modern butchering experiment and comparing the replicas with their prehistoric counterparts, the researchers determined that the hand axe was probably prehistoric humanity’s sturdy “Swiss army knife,” capable of cutting and breaking down bone, tough sinew, and hide. The slimmer, more delicate scraper was used to separate fur and animal fat from muscle tissue.

“Prehistoric peoples made use of all parts of the animal,” explains Barkai. “In the case of the massive elephant, for example, they would have needed to use both tools to manage such a challenging task. In this thousand-piece puzzle called archaeology, sometimes we find pieces that connect other pieces together. This is what we have found with the stone tools and animal bones.”

This research on ancient humans and prehistoric stone tools is published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Top Image: Prehistoric stone tools: An elephant rib bearing marks from flint tools at the Revadim site. (Photo courtesy of American Friends of Tel Aviv University)