Pathogens Perish on Laser-Treated Metal

Pathogens perish on contact with etched copper, according to a new study using the antimicrobial properties of copper and laser technology.

In a world where every doorknob, handle, and gas pump seems suspicious, there’s good news out of Purdue University: a team of engineers has figured out how to make some surfaces kill certain pathogens on contact.

Rough and ready

According to Rahim Rahimi, leader of the 11-person research team and a materials engineering assistant professor at Purdue, the antimicrobial effects of copper have been known and used for hundreds of years. When bacterial pathogens like E. coli or MRSA fall on surfaces, their outer membranes can rupture, which eventually kills them. But bacteria that survive can still linger on smooth surfaces for hours, leaving a wide window for transmission through contact.

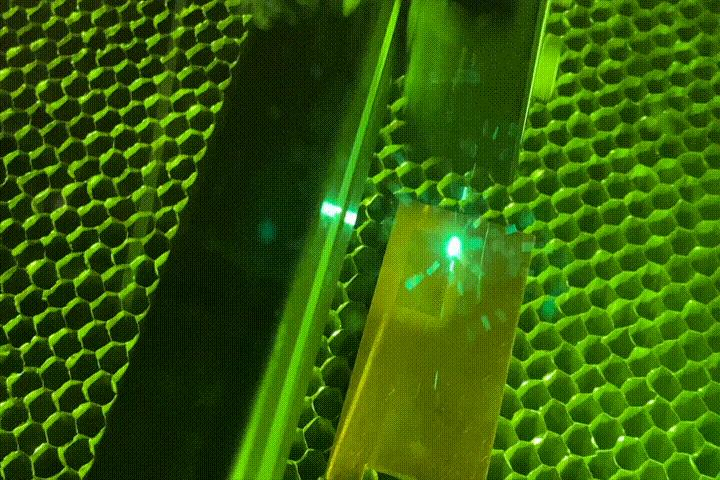

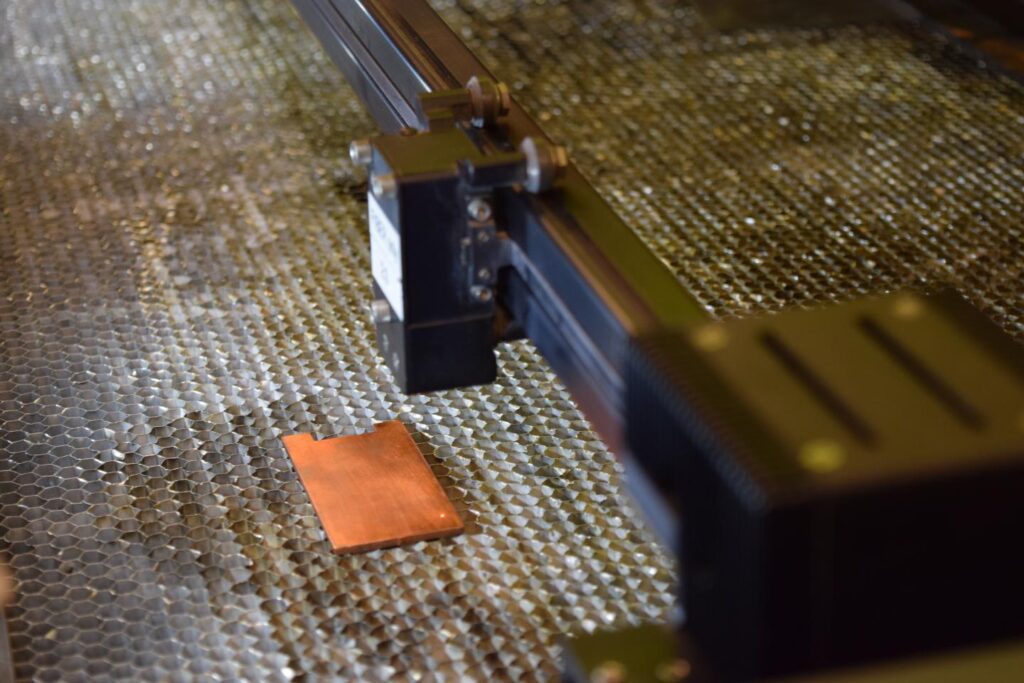

Using lasers to etch in patterns on a level too small for the human eye to see, Rahimi’s team roughened up typically smooth copper plates, increasing the surface area that’s lethal to microbes, then watched the pathogens perish. Under a microscope in a supplemental YouTube video (below), the difference is clear: non-treated copper is relatively uniform, with a few scratches and dents, but the laser-treated copper is a veritable jungle of grooves, craters, swirls, and bumps.

Tackling deadly bacterial pathogens

This laser treatment technique isn’t yet capable of eradicating viruses such as COVID-19, since viruses are much smaller than bacteria and therefore harder to kill. But the study found that this technique was effective against strains of well-known deadly pathogens such as E. coli and antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” like MRSA.

In their analysis, the team found that the laser-treated copper surfaces only needed one hour to completely eradicate a highly concentrated strain of E. coli, and less than two hours to kill other pathogens they tested.

With antibiotics making certain strains more challenging to fight, an antibiotic-free method of killing bacteria could be highly beneficial, possibly even helping minimize the development of superbugs in the first place.

A simple solution

The process’s simplicity could also make antimicrobial surfaces like this more common someday. A press release from the university deems this laser treatment technique scalable and easily applied to other surfaces and devices. Rahimi highlights its direct application, noting in the YouTube video that the process doesn’t involve any additional materials, coatings, or chemicals applied to the etched surfaces.

“We’ve created a robust process that selectively generates micron and nanoscale patterns directly onto the targeted surface without altering the bulk of the copper material,” he says in the press release.

While “nanomaterial coatings” have been used on metal surfaces in the past, they can leach chemicals into the environment, creating problems beyond the ones they solve. With laser treatment, the metal itself is changed, eliminating the need for other substances to have the same effect.

RELATED: NEW, DURABLE SELF-CLEANING SURFACES

Other uses inside the body

The potential positives of laser-treated copper don’t stop with simple solutions and killing bacteria. Rahimi’s team observed another use of the technology: encouraging bone growth when laser-treated copper is used as an implant in the human body.

The team found that the treated material became hydrophilic, meaning it’s easily wet with water. This means the material could work well in implants that help with bone repair or replacement, since bone cells have an easier time attaching to hydrophilic surfaces. Through observing the effect of fibroblast cells—the most common connective tissue cells in our bodies—the team learned that laser-treated copper allowed cells to attach more thoroughly than non-treated copper, helping better integrate the implant into the body over time.

The research team is already exploring more uses for this laser treatment on surfaces and substances beyond copper. Since the study’s publication earlier this year, the lab—which specializes in developing materials to address problems in healthcare—has experimented with other materials typically used for implants and wound treatment, taking steps toward a future that’s a little cleaner, safer, and healthier for us all.

This study was published in the journal Advanced Materials Interfaces.

Featured image: A laser treats the surface of copper, giving it a texture that would allow the metal to instantly kill bacteria. (Purdue University/Erin Easterling)

Reference

Selvamani, V., Zareei, A., Elkashif, A., Maruthamuthu, M., Chittiboyina, S., Delisi, D., Li, Z., Cai, L., Pol, V., Seleem, M., & Rahimi, R. (2020). Hierarchical micro/mesoporous copper structure with enhanced antimicrobial property via laser surface texturing. Advanced Materials Interfaces, 7(7), 1901890. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201901890

About the Author

Mackenzie Myers is a science writer, avid knitter, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again. She lives in Michigan with her husband, her cat and a plethora of houseplants.